The US presidential election might be closer than the polls suggest (if we can trust them this time)

- Written by Simon Jackman, Chief Executive Officer, US Studies Centre, University of Sydney

With less than two months until the US presidential election, Democratic nominee Joe Biden leads incumbent Donald Trump in the bulk of opinion polls.

But poll-based election forecasts have proved problematic before. The polls were widely maligned after the 2016 election because Trump won the election when the majority of the polling said he would not.

What went wrong with the polls in 2016? And is polling to be believed this time around, or like in 2016, are the polls substantially underestimating Trump’s support?

Read more: How did we get the result of the US election so wrong?

Swing states decide US presidential elections

US presidential elections are two-stage, state-by-state contests.

States are allocated delegates roughly proportional to their populations, with 538 delegates in total. The votes of Americans then decide who wins the delegates in the Electoral College.

In almost all states, the candidate who has the highest vote total takes all the delegates for that state. The candidate who wins a majority (270 or more) of the Electoral College wins the election.

Biden has been spending more time in the crucial state of Pennsylvania, where he holds a slim lead over Trump in many polls.

Mary Altaffer/AP

Biden has been spending more time in the crucial state of Pennsylvania, where he holds a slim lead over Trump in many polls.

Mary Altaffer/AP

For the fifth time in American history, the 2016 election produced a mismatch between the national popular vote and the Electoral College outcome. Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate, won nearly 2.9 million more votes than Trump, yet still lost the election.

Trump won states efficiently, by razor-thin margins in some cases, converting 46% of all votes cast into 56.5% of the Electoral College. Conversely, Clinton’s huge popular vote tally was concentrated in big states such as California and New York.

For this reason, election analysts focus less on national polls and more on polls from “swing states”.

These are states that have swung between the parties in recent presidential elections (for example, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Florida and North Carolina), or could be on the verge of swinging (Arizona, Texas, Georgia and Minnesota).

These states — even as few as two or three of them — will decide the 2020 election.

State polls currently point to a Biden win

As part of a large research project at the United States Studies Centre, we have compiled data from polling averages in all the swing states going back to 120 days before the election and compared them to the same time periods in 2016. Our goal was to provide a key point of reference to more correctly read the polls in 2020.

The charts for all swing states can be found here.

Our research shows Biden currently has poll leads in several states that went for Barack Obama in 2008 and/or 2012 and then swung to Trump in 2016, such as Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. These five states are worth 90 Electoral College votes.

Biden also leads the polls in consistently Republican-voting Arizona (11 electoral votes).

So, if we take recent polls in these states at face value, then Trump would lose 101 of the Electoral College votes he won in 2016 and be soundly defeated.

Biden has already visited Wisconsin on the campaign trail — something Clinton failed to do in 2016.

Tannen Maury/EPA

Biden has already visited Wisconsin on the campaign trail — something Clinton failed to do in 2016.

Tannen Maury/EPA

Why did state polls perform poorly in 2016?

But state polls were heavily criticised in 2016 for underestimating Trump’s support, as these charts in our research highlight.

The final poll averages in 2016 underestimated Trump’s margin over Clinton by more than five points in several swing states: North Carolina (5.3), Iowa (5.7), Minnesota (5.7), Ohio (6.9) and Wisconsin (7.2). This is calculated by taking the difference between the official election result and the average of the polls on election eve.

A review of 2016 polling by the American Association of Public Opinion Research examined a number of hypotheses about the bias of state-level polls in 2016.

Two predominant factors made the difference:

1. An usually large number of late-deciders strongly favoured Trump

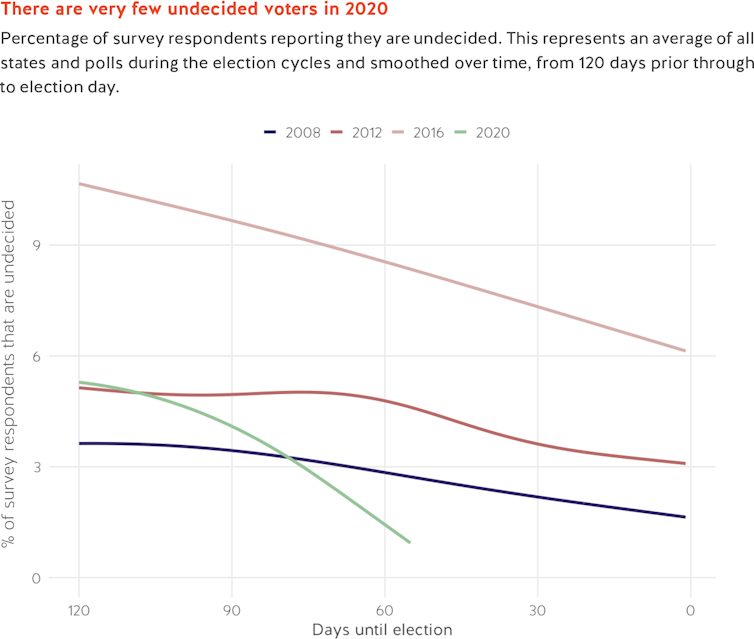

The number of “undecideds” in 2016 was more than double that in prior elections. Of these, a disproportionate number voted for Trump.

But 2020 polling to date reveals far fewer undecided voters, suggesting this source of poll error will not be as large in this year’s election.

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

2. Changes in voter turnout

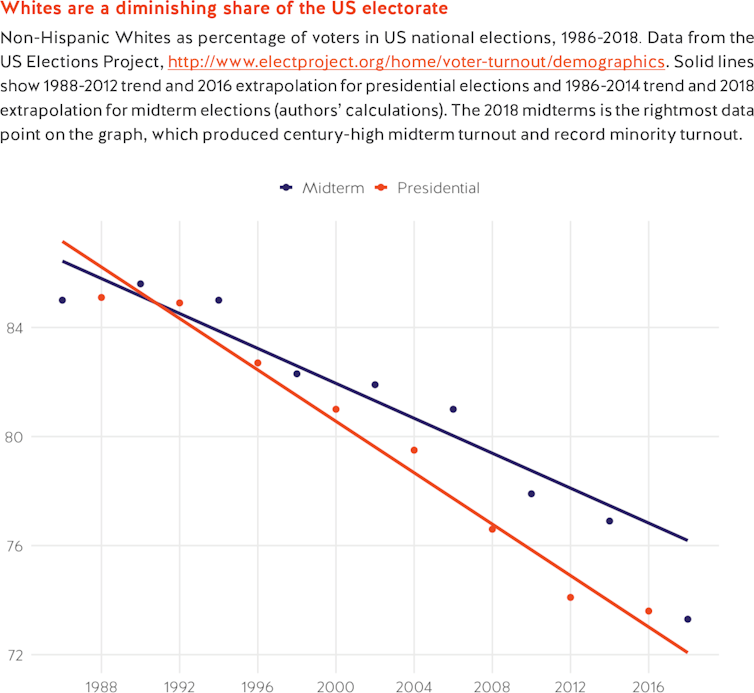

In 2016, Trump successfully mobilised white voters who are becoming a smaller portion of the American electorate and ordinarily have low rates of voter turnout. These were largely non-urban voters and those with lower levels of education.

This year will likely see high levels of engagement from both sides — and potentially a surge in turnout unseen in decades — which could further undermine the accuracy of election polls.

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

2. Changes in voter turnout

In 2016, Trump successfully mobilised white voters who are becoming a smaller portion of the American electorate and ordinarily have low rates of voter turnout. These were largely non-urban voters and those with lower levels of education.

This year will likely see high levels of engagement from both sides — and potentially a surge in turnout unseen in decades — which could further undermine the accuracy of election polls.

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Re-interpreting the 2020 polls

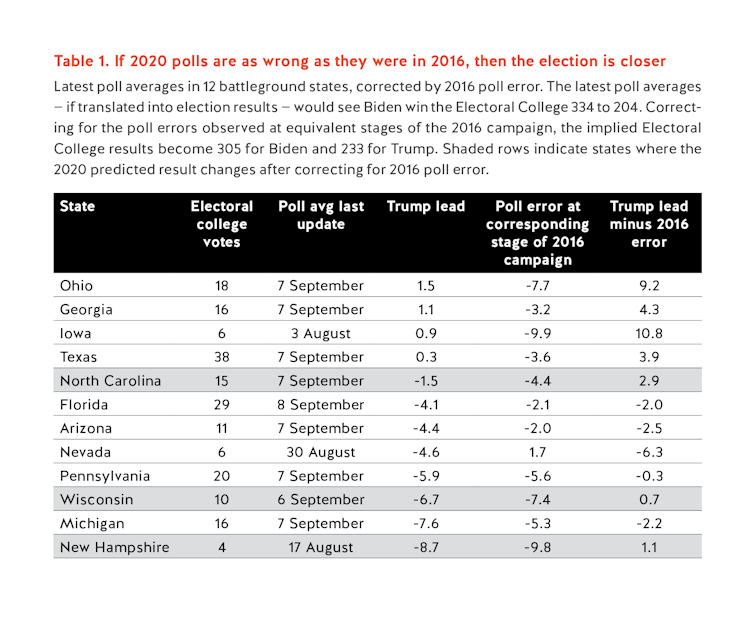

The latest state poll averages imply Biden will handily win the election with an Electoral College victory of 334 to 204.

But if the 2020 polls are as wrong as they were in 2016, then Biden’s current poll leads in New Hampshire, North Carolina and Wisconsin are misleading. If Biden loses these three states, the Electoral College result will be 305-233, still a comfortable Biden win.

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Re-interpreting the 2020 polls

The latest state poll averages imply Biden will handily win the election with an Electoral College victory of 334 to 204.

But if the 2020 polls are as wrong as they were in 2016, then Biden’s current poll leads in New Hampshire, North Carolina and Wisconsin are misleading. If Biden loses these three states, the Electoral College result will be 305-233, still a comfortable Biden win.

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

In recent weeks, however, we have seen Biden’s poll leads in Pennsylvania and Florida be smaller than the corresponding poll error in those states from 2016.

If Trump wins these two large states (in addition to New Hampshire, North Carolina and Wisconsin), and the other 2016 results are replicated elsewhere, then he will narrowly win the election with 282 Electoral College votes.

Given the statistical range of poll errors seen in 2016 — and assuming they reoccur in 2020 — current polling implies Trump has roughly a one in three chance of winning re-election.

Read more:

Winning the presidency won't be enough: Biden needs the Senate too

What other factors will come into play?

The COVID-19 pandemic and controversies around the administration of the election could further jeopardise the validity of 2020 polling. Official statistics already show many voters are attempting to make use of voting by mail or in-person, early voting.

Access to these alternative forms of voting varies tremendously across the United States, so the political consequences are difficult to anticipate.

Trump and his Republican supporters have raised doubts about the validity and security of vote by mail. A recent opinion poll showed Democrats are much more likely to rely on vote by mail compared to Republicans (72% to 22%).

United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

In recent weeks, however, we have seen Biden’s poll leads in Pennsylvania and Florida be smaller than the corresponding poll error in those states from 2016.

If Trump wins these two large states (in addition to New Hampshire, North Carolina and Wisconsin), and the other 2016 results are replicated elsewhere, then he will narrowly win the election with 282 Electoral College votes.

Given the statistical range of poll errors seen in 2016 — and assuming they reoccur in 2020 — current polling implies Trump has roughly a one in three chance of winning re-election.

Read more:

Winning the presidency won't be enough: Biden needs the Senate too

What other factors will come into play?

The COVID-19 pandemic and controversies around the administration of the election could further jeopardise the validity of 2020 polling. Official statistics already show many voters are attempting to make use of voting by mail or in-person, early voting.

Access to these alternative forms of voting varies tremendously across the United States, so the political consequences are difficult to anticipate.

Trump and his Republican supporters have raised doubts about the validity and security of vote by mail. A recent opinion poll showed Democrats are much more likely to rely on vote by mail compared to Republicans (72% to 22%).

Thousands of Trump supporters take part in a caravan rally in Florida, one of the critical battleground states in the election.

Cristobel Herrera-Ulashkevich/EPA

Unsurprisingly, Democrats and other groups are bringing numerous lawsuits to help ensure vote by mail remains a widely available method of voting.

It is quite likely the courts will be asked to rule on the validity of the results after the election, on the basis mail ballots have been either improperly included or excluded in official tallies.

So, will it be closer than expected?

On the one hand, this year’s election seems to have historically low levels of undecided voters, a factor that should make polls more accurate. But offsetting this is tremendous uncertainty about turnout and whose votes will be cast and counted.

All this suggests considerable caution be exercised in relying on the polls to forecast the election. These forecasts are almost surely overconfident.

The other main takeaway: Trump’s chances of re-election are likely higher than suggested by the polling we have seen to date.

The charts in this piece were initially created by Zoe Meers, formerly a data visualisation analyst at the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Thousands of Trump supporters take part in a caravan rally in Florida, one of the critical battleground states in the election.

Cristobel Herrera-Ulashkevich/EPA

Unsurprisingly, Democrats and other groups are bringing numerous lawsuits to help ensure vote by mail remains a widely available method of voting.

It is quite likely the courts will be asked to rule on the validity of the results after the election, on the basis mail ballots have been either improperly included or excluded in official tallies.

So, will it be closer than expected?

On the one hand, this year’s election seems to have historically low levels of undecided voters, a factor that should make polls more accurate. But offsetting this is tremendous uncertainty about turnout and whose votes will be cast and counted.

All this suggests considerable caution be exercised in relying on the polls to forecast the election. These forecasts are almost surely overconfident.

The other main takeaway: Trump’s chances of re-election are likely higher than suggested by the polling we have seen to date.

The charts in this piece were initially created by Zoe Meers, formerly a data visualisation analyst at the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Authors: Simon Jackman, Chief Executive Officer, US Studies Centre, University of Sydney