Does Victoria's second wave suggest we should debate an elimination strategy?

- Written by Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

Scott Morrison summoned his self-restraint and resisted temptation. Invited on Thursday to attack the Victorian government over its disastrous decision to use private security guards to monitor people in hotel quarantine, the prime minister was careful.

He hadn’t seen himself as a “commentator” on state governments, he said. “I’ve seen myself simply seeking to help them deal with the problems that they’ve had.”

He added just a little dig, saying he understood many Victorians would be frustrated and angry and “I’m aware of where they’re directing that frustration and anger.”

“But it won’t help the situation if I were to engage in any of that. I have a good working relationship with the Victorian government.”

Morrison needs to keep his national cabinet as united as possible, and turning on Victoria would be counterproductive.

The cynics might also note there’s no imminent election in Victoria. Contrast the federal criticism of the Palaszczuk government, which goes to the polls in October, over its refusal to open its border (which it is finally doing this Friday, except to Victorians).

Federal Liberals from Victoria are sending mixed messages. Tim Wilson told Sky the Andrews government had put the interests of companies “that hired their union mates” above the public health of citizens.

But Russell Broadbent said now was the time to be “backing the premier, not attacking the premier. This is not a time for politics and divisions. We all make mistakes.”

This second wave of the coronavirus that’s hit Victoria will test whether the strong public support we’ve seen for Australian leaders during COVID will hold.

Morrison is being diplomatic but Daniel Andrews this week has come under intense criticism, especially from sections of the media, with calls for ministerial heads and greater accountability. Andrews’ decision to appoint a judicial inquiry into the quarantine disaster has been condemned as a way of avoiding having to answer immediate questions.

The premier was particularly exposed because early on, he had been so insistant there should be tough restrictions.

The reporting has also, naturally enough, focussed on the hardships stories. But it is yet to become clear what the majority of the community thinks, or how much more difficult the drastic new lockdown will be to run than the last one.

On treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s figures the lockdown will cost the Victorian economy $1 billion a week – and it goes for six weeks.

The rest of the country will pay for the mistakes and lapses in Victoria, even if it will be some time before we know how high the price will be.

The new situation will reset the parameters for the federal government’s July 23 economic statement, with even more spending needed after September than was anticipated.

The government is now framing that statement against a background of greater uncertainty than expected only weeks ago.

The Victorian outbreak has meant the state has not been able to accept flights of Australians returning from overseas. Other states want inflows of returnees restricted and national cabinet is set to cap numbers generally, adding to the hurdles faced by those who have delayed coming home. Federal and state governments are showing little sympathy for these laggards, believing they should have returned earlier.

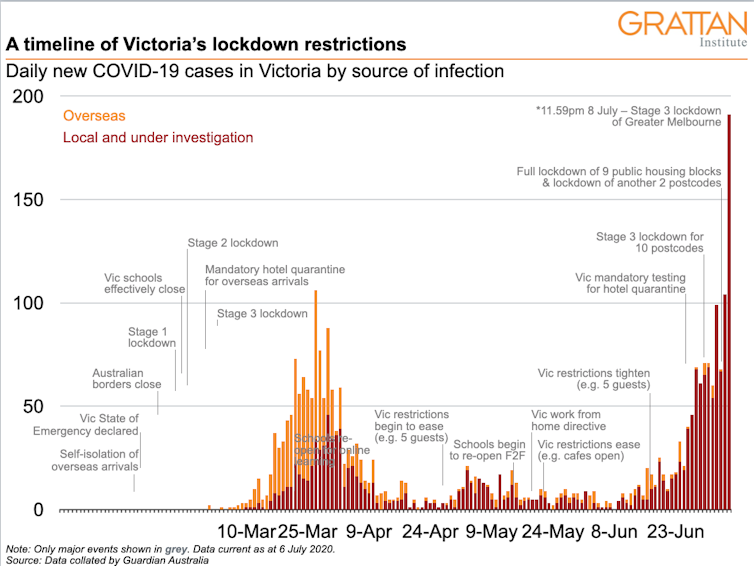

Grattan Institute, Author provided

On another front, the new outbreak means the hoped-for Tasman bubble – opening of travel between Australia and New Zealand - now seems a distant prospect, certainly at a national level. The Australian National University and the University of Canberra have delayed plans to bring back some overseas students.

If the second wave moves interstate, the consequences could be dire. No wonder premiers are erecting walls against Victorians. ACT chief minister Andrew Barr has even suggested some Victorian federal parliamentary backbenchers might be encouraged to stay at home.

A broader second wave would make the October budget much more difficult. Potentially it could become near impossible to pursue the substantial reform agenda which Morrison has flagged he wants. The government is talking about bringing forward the legislated tax cuts but that is not new reform.

The Victorian situation has reignited the issue of whether Australia should pursue an elimination strategy, rather than a suppression one.

Morrison, with an eye to the economy, early on embraced suppression.

He and the federal health authorities warned, as the economy’s reopening began, that there would be spikes – localised outbreaks that would have to be dealt with.

What was perhaps not adequately appreciated was the fine line between spikes and a new “wave”.

Admittedly an elimination strategy would not have prevented an outbreak caused by a lapse in quarantine arrangements for overseas returnees, although it might have been easier to control.

Morrison always preferred the suppression strategy because he thought the economic costs of pitching for “elimination” would be too high. But the cost-benefit weighting did depend on the “suppression” model working.

The benefits of elimination, despite the greater short-term pain of tougher lockdowns, are to be seen in New Zealand. As of Thursday there were 24 cases there, all overseas returnees and all in hotel quarantine. There is currently no community transmission. The NZ health ministry said it had been 69 days since the last case was acquired locally from an unknown source. The economy has been able to reopen.

Read more:

Melbourne's hotel quarantine bungle is disappointing but not surprising. It was overseen by a flawed security industry

The question is whether elimination would be practical for a bigger country like Australia. Some experts believe so.

Former secretary of the federal health department Stephen Duckett is arguing for an elimination approach to be adopted even now.

Duckett, with the Grattan Institute, and Will Mackey this week wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald that the Melbourne situation “lays bare the uncertainty that comes with the nation’s suppression strategy”.

“Australia’s national cabinet should explicitly pursue an elimination strategy similar to that of New Zealand. The current suppression strategy carries the certainty of repeated outbreaks and lockdowns, shattering business confidence, confusing the public, and prolonging the COVID-19 ordeal,” they wrote.

“It will cost the economy more than an elimination strategy. If we reassess and refocus, the benefits of elimination are within our reach. If not, we must all prepare to live with uncertainty.”

Health minister Greg Hunt dismissed of Duckett’s call, telling the ABC “to pretend we can wish the disease away is not … a realistic or responsible statement”.

In fact a number of states have in effect been pursuing elimination, through their border policies, and this has been largely successful.

But nationally, the suppression versus elimination debate is one that we’ve never properly had. Maybe it’s time we did.

Grattan Institute, Author provided

On another front, the new outbreak means the hoped-for Tasman bubble – opening of travel between Australia and New Zealand - now seems a distant prospect, certainly at a national level. The Australian National University and the University of Canberra have delayed plans to bring back some overseas students.

If the second wave moves interstate, the consequences could be dire. No wonder premiers are erecting walls against Victorians. ACT chief minister Andrew Barr has even suggested some Victorian federal parliamentary backbenchers might be encouraged to stay at home.

A broader second wave would make the October budget much more difficult. Potentially it could become near impossible to pursue the substantial reform agenda which Morrison has flagged he wants. The government is talking about bringing forward the legislated tax cuts but that is not new reform.

The Victorian situation has reignited the issue of whether Australia should pursue an elimination strategy, rather than a suppression one.

Morrison, with an eye to the economy, early on embraced suppression.

He and the federal health authorities warned, as the economy’s reopening began, that there would be spikes – localised outbreaks that would have to be dealt with.

What was perhaps not adequately appreciated was the fine line between spikes and a new “wave”.

Admittedly an elimination strategy would not have prevented an outbreak caused by a lapse in quarantine arrangements for overseas returnees, although it might have been easier to control.

Morrison always preferred the suppression strategy because he thought the economic costs of pitching for “elimination” would be too high. But the cost-benefit weighting did depend on the “suppression” model working.

The benefits of elimination, despite the greater short-term pain of tougher lockdowns, are to be seen in New Zealand. As of Thursday there were 24 cases there, all overseas returnees and all in hotel quarantine. There is currently no community transmission. The NZ health ministry said it had been 69 days since the last case was acquired locally from an unknown source. The economy has been able to reopen.

Read more:

Melbourne's hotel quarantine bungle is disappointing but not surprising. It was overseen by a flawed security industry

The question is whether elimination would be practical for a bigger country like Australia. Some experts believe so.

Former secretary of the federal health department Stephen Duckett is arguing for an elimination approach to be adopted even now.

Duckett, with the Grattan Institute, and Will Mackey this week wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald that the Melbourne situation “lays bare the uncertainty that comes with the nation’s suppression strategy”.

“Australia’s national cabinet should explicitly pursue an elimination strategy similar to that of New Zealand. The current suppression strategy carries the certainty of repeated outbreaks and lockdowns, shattering business confidence, confusing the public, and prolonging the COVID-19 ordeal,” they wrote.

“It will cost the economy more than an elimination strategy. If we reassess and refocus, the benefits of elimination are within our reach. If not, we must all prepare to live with uncertainty.”

Health minister Greg Hunt dismissed of Duckett’s call, telling the ABC “to pretend we can wish the disease away is not … a realistic or responsible statement”.

In fact a number of states have in effect been pursuing elimination, through their border policies, and this has been largely successful.

But nationally, the suppression versus elimination debate is one that we’ve never properly had. Maybe it’s time we did.

Authors: Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra