Can government actually predict the jobs of the future?

- Written by David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

The future of jobs has been used to justify the major changes to university education announced last week. Fees for courses that, according to the government, lead to jobs with a great future will fall, while those with a poor future will rise.

But can the government predict the jobs of the future? And do proposed fee changes match those jobs that will grow?

It’s hard to predict future jobs

In the research I have done on the future of work, several things are clear. The further you look ahead, the less useful the present is as a guide. This is especially the case in employment because, in a quickly changing world, technology is hard to predict and changing consumption patterns even harder.

As prices for products fall in the face of new technologies, and new products are invented, those future consumption patterns are crucial but unforeseeable. Otherwise, we would all be using beta video camcorders but not the cameras on mobile phones.

Still, there have been several attempts to look at the jobs of the future, including by European researchers, the US Bureau of Labour Statistics, the CSIRO and the Australian government itself. There have been studies on future automation from Oxford university and the OECD.

From these we can tell some factors that will be important.

These include the ageing population and the increasing demands that will be put onto care workers. In the short to medium term, it is clear care work will be a major area of growth. But it is a lot harder to judge in the long term.

Artificial intelligence means it is no longer just routine jobs (remember typists?) that are threatened by new technology.

Information and communications technology (ICT) occupations may be strategically important but they need not provide lots of jobs. Computer programming may be done by other computers, for instance. Projected employment growth for ICT managers to 2024 (1.2%) is barely one sixth the average for all jobs (8.3%). Some jobs in ICT might end up quite insecure.

The type of skills (or competencies) that will likely be in demand appear to be those relating to creativity, problem-solving, collaboration, cooperation, resilience, communication, complex reasoning, social interaction and emotional intelligence.

They include empathy-related competencies such as compassion, tolerance, inter-cultural understanding, pro-social behaviour and social responsibility.

Some of these are what universities preferred to call “critical thinking” skills – the sorts developed by generalist degrees like arts and commerce.

Choosing exactly the right field for a degree is less important, in terms of getting a job, than simply doing one. Reflecting the constant pressure of credentialism, employers will demand a more educated workforce (and continue to complain it is not “work ready”), regardless of universities’ or governments’ ability to anticipate the skill needs of the future.

Fee changes and future jobs

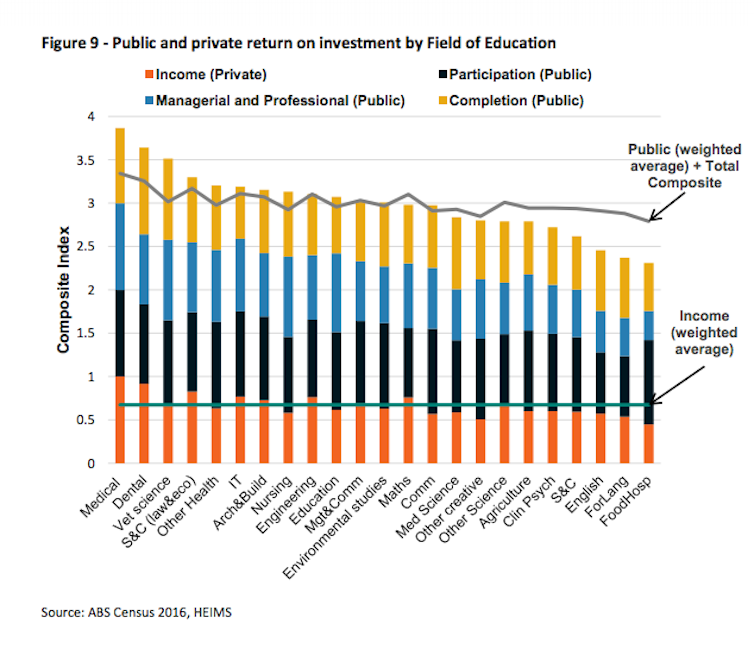

The government claimed higher personal incomes (“private returns”) from studying its preferred courses explained the different fees structure in its reforms. That’s how it justified raising fees for humanities, business and commerce courses while reducing fees for ICT, engineering and science.

But its own data actually showed there was no correlation between the two.

Job-Ready Graduates: Higher Education Reform Package 2020 (screenshot Figure 9)

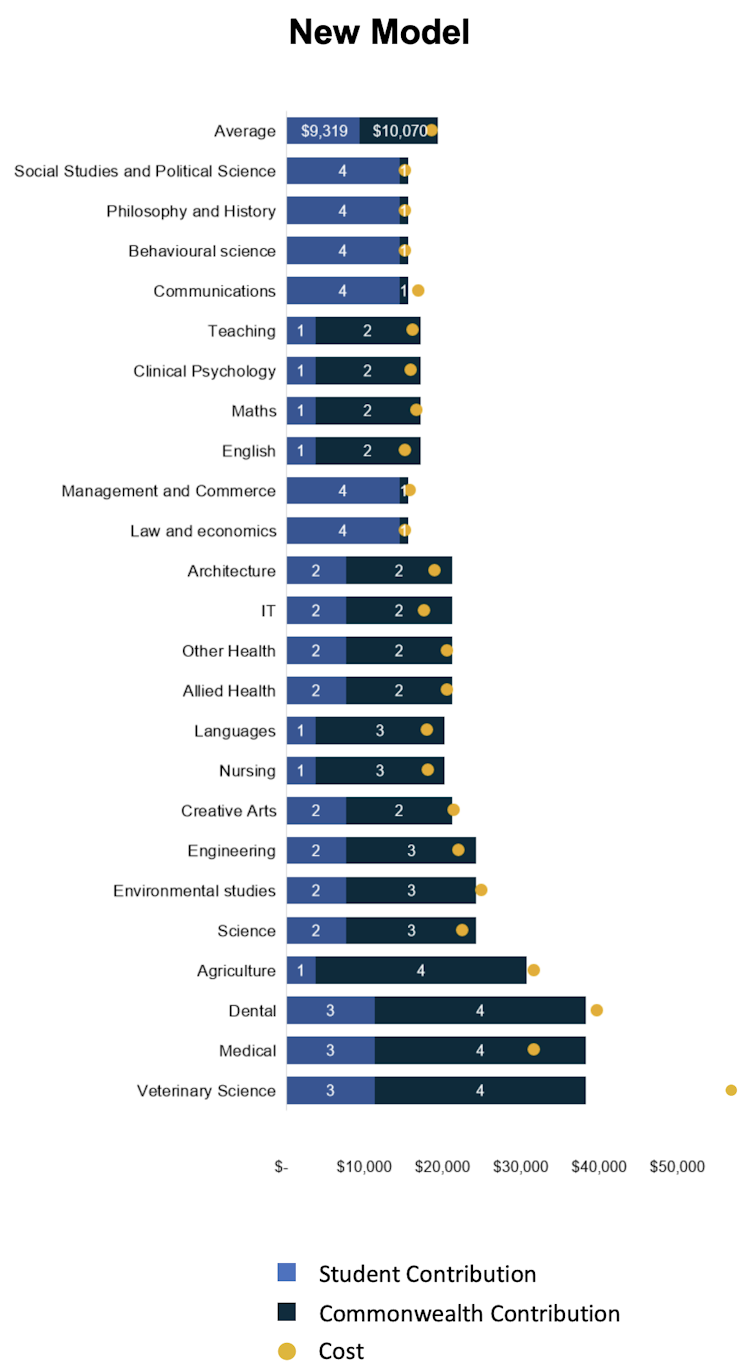

For example, by the logic of government policy, law and economics should have the fourth lowest student fees because their figures (see the chart above) show the expected private returns from law and economics courses are the fourth best. Yet the fees for law and economics under the proposed schema are equal worst (band 4, in the chart below).

The student fees for management and commerce, by their logic, should be right in the middle of the fee range as the returns are in the middle. Yet their fees are also equal highest.

Job-Ready Graduates: Higher Education Reform Package 2020 (screenshot Figure 9)

For example, by the logic of government policy, law and economics should have the fourth lowest student fees because their figures (see the chart above) show the expected private returns from law and economics courses are the fourth best. Yet the fees for law and economics under the proposed schema are equal worst (band 4, in the chart below).

The student fees for management and commerce, by their logic, should be right in the middle of the fee range as the returns are in the middle. Yet their fees are also equal highest.

Job-Ready Graduates: Higher Education Reform Package 2020 (screenshot Figure 10)

And the government did not even use future-facing data to estimate private returns. It used census data from 2016 – on-average earnings in the census year. These did not account for the year a qualification was obtained.

That was a major gap, as returns tend to increase as time since graduation grows. These estimates made no use of the government’s own employment projections that suggested, for example, that employment for “industrial, mechanical and production engineers” would fall by 1.3%.

So it is hard to believe, even if the government thought it could predict the jobs of the future, that this is what motivated the changes to fees.

Read more:

Humanities graduates earn more than those who study science and maths

After all, in many areas where student fees are cut, government contributions are also cut — by more. The resources to universities to provide the content of the future will be reduced. For instance, science and engineering courses will see a 17% reduction per student per year.

A more plausible explanation for the changes to university fees is that the marketable skills argument is just a cover for another agenda.

Critical thinking is a key skill for the future, but one can’t help but think it is not something the government wants encouraged.

Job-Ready Graduates: Higher Education Reform Package 2020 (screenshot Figure 10)

And the government did not even use future-facing data to estimate private returns. It used census data from 2016 – on-average earnings in the census year. These did not account for the year a qualification was obtained.

That was a major gap, as returns tend to increase as time since graduation grows. These estimates made no use of the government’s own employment projections that suggested, for example, that employment for “industrial, mechanical and production engineers” would fall by 1.3%.

So it is hard to believe, even if the government thought it could predict the jobs of the future, that this is what motivated the changes to fees.

Read more:

Humanities graduates earn more than those who study science and maths

After all, in many areas where student fees are cut, government contributions are also cut — by more. The resources to universities to provide the content of the future will be reduced. For instance, science and engineering courses will see a 17% reduction per student per year.

A more plausible explanation for the changes to university fees is that the marketable skills argument is just a cover for another agenda.

Critical thinking is a key skill for the future, but one can’t help but think it is not something the government wants encouraged.

Authors: David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

Read more https://theconversation.com/can-government-actually-predict-the-jobs-of-the-future-141275