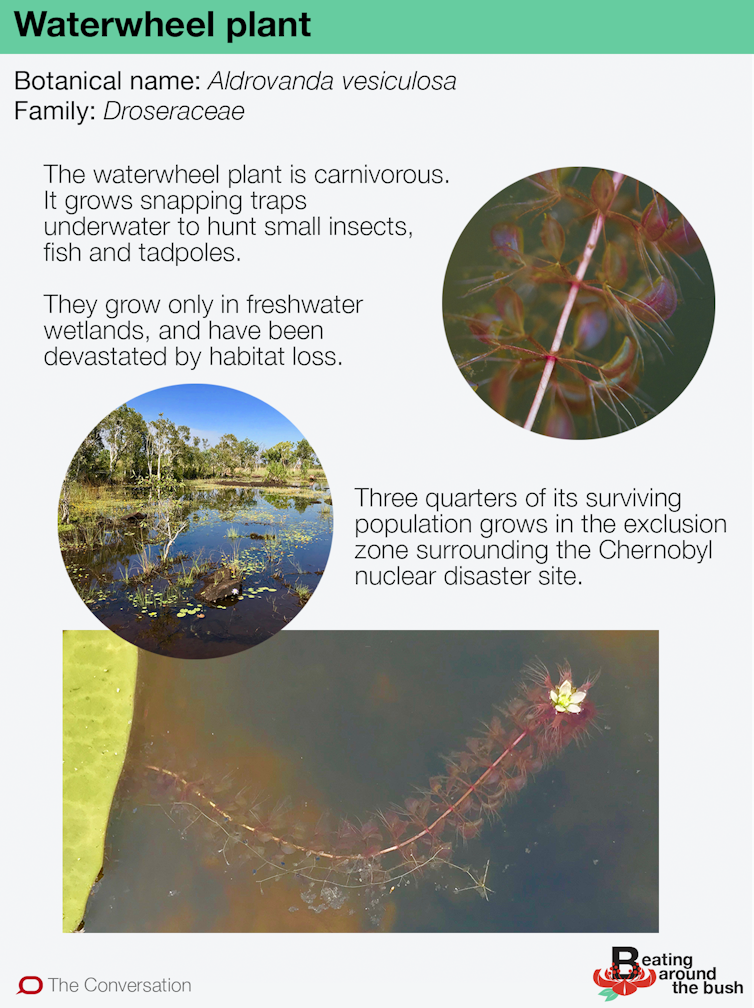

The waterwheel plant is a carnivorous, underwater snap-trap

- Written by Adam Cross, Research Fellow, Curtin University

Sign up to the Beating Around the Bush newsletter here, and suggest a plant we should cover at batb@theconversation.edu.au.

Billabongs in the northern Kimberley are welcome oases of colour in an otherwise brown landscape. This one reflected the clear blue sky, broken up by water lilies and a scattering of yellow Nymphoides flowers. A ring of trees surrounded it, taking advantage of the permanent water source.

My student and I approached with excitement. We had spent a week searching barren habitats, but now on the final day of our expedition we were ecstatic about the potential of this watering hole.

Read more: The strange world of the carnivorous plant

Between us we had been plant-hunting in northern Australia for nearly 20 years and knew well that where water seeped over sandstone, carnivorous plants often grew.

Hunting carnivorous plants in the North Kimberley.

Adam Cross, Author provided

Hunting carnivorous plants in the North Kimberley.

Adam Cross, Author provided

Clambering along some rocks at the edge of the billabong, I looked down by chance into a small rockhole and nearly fell in. Floating between two water lily leaves was a short stem of whorled leaves. And at the end of each leaf, a tiny snapping trap.

Looking out into the middle of the billabong I saw thousands of plants, and even a few tiny white flowers protruding above the surface of the water. After a decade of fruitlessly searching the swamps, creeks and rivers of the Kimberley for it, I had stumbled across a new population of Aldrovanda vesiculosa, the waterwheel plant.

The Conversation

The waterwheel plant must surely be among the most fascinating plants in the world. Its genus dates back 50 million years, and although we know of many species from the fossil record, A. vesiculosa is the only modern species.

The waterwheel plant is a submerged aquatic plant, first discovered by botanists in 1696 and studied by the likes of Charles Darwin, and is the only species to have evolved snap-trap carnivory under water. It takes just 100 milliseconds for the snapping leaves to close upon small, unsuspecting aquatic invertebrates such as mosquito larvae – one of the fastest movements in the plant kingdom.

Although the waterwheel plant also photosynthesises, it needs to eat prey to get enough nutrients to grow. And while its traps may be small, up to 1cm long, it can efficiently catch tiny insects and even small fish and tadpoles.

Mr Worldwide

Uniquely, the waterwheel plant is a global clone, with virtually no genetic differentiation between populations on different continents.

It has one of the largest and most disconnected distributions of any flowering species, growing in more than 40 countries across four continents, from sub-Arctic regions of northern Russia to the southern coast of Australia, and from western Africa to the eastern coast of Australia. Yet despite this global distribution, the waterwheel plant occupies a very small ecological niche, and grows only in the shallow and acidic waters of nutrient-poor freshwater swamps.

The waterwheel plant is sensitive, and is often the first species to disappear when these habitats become degraded.

As a result, this unique species has undergone a catastrophic global decline as humans have systematically degraded and destroyed nearly two-thirds of the world’s wetland habitats.

The past century has seen the systematic extinction of the waterwheel plant from more than half the countries it once occupied, and a rapid deterioration in almost all others. From more than 400 populations recorded since the 18th century, fewer than 50 now remain.

Three-quarters of these are in the exclusion zone surrounding the Chernobyl nuclear disaster site, with the rest spread thinly across Africa, Australia and Europe, and isolated from each other by thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands, of kilometres. The species can be seen as a harbinger of the perilous state of our world’s freshwater ecosystems.

The Conversation

The waterwheel plant must surely be among the most fascinating plants in the world. Its genus dates back 50 million years, and although we know of many species from the fossil record, A. vesiculosa is the only modern species.

The waterwheel plant is a submerged aquatic plant, first discovered by botanists in 1696 and studied by the likes of Charles Darwin, and is the only species to have evolved snap-trap carnivory under water. It takes just 100 milliseconds for the snapping leaves to close upon small, unsuspecting aquatic invertebrates such as mosquito larvae – one of the fastest movements in the plant kingdom.

Although the waterwheel plant also photosynthesises, it needs to eat prey to get enough nutrients to grow. And while its traps may be small, up to 1cm long, it can efficiently catch tiny insects and even small fish and tadpoles.

Mr Worldwide

Uniquely, the waterwheel plant is a global clone, with virtually no genetic differentiation between populations on different continents.

It has one of the largest and most disconnected distributions of any flowering species, growing in more than 40 countries across four continents, from sub-Arctic regions of northern Russia to the southern coast of Australia, and from western Africa to the eastern coast of Australia. Yet despite this global distribution, the waterwheel plant occupies a very small ecological niche, and grows only in the shallow and acidic waters of nutrient-poor freshwater swamps.

The waterwheel plant is sensitive, and is often the first species to disappear when these habitats become degraded.

As a result, this unique species has undergone a catastrophic global decline as humans have systematically degraded and destroyed nearly two-thirds of the world’s wetland habitats.

The past century has seen the systematic extinction of the waterwheel plant from more than half the countries it once occupied, and a rapid deterioration in almost all others. From more than 400 populations recorded since the 18th century, fewer than 50 now remain.

Three-quarters of these are in the exclusion zone surrounding the Chernobyl nuclear disaster site, with the rest spread thinly across Africa, Australia and Europe, and isolated from each other by thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands, of kilometres. The species can be seen as a harbinger of the perilous state of our world’s freshwater ecosystems.

Waterwheel plants flourish in this oasis in the remote North Kimberley.

Adam Cross, Author provided

Conservation

Ecologists are working hard at conserving the waterwheel plant: monitoring habitats, reintroducing it into areas where it has become extinct and detailed study of its ecology and reproductive biology.

But ultimately, its future depends on the survival of wetlands – complex and sensitive ecosystems that can be affected by even small changes throughout their catchment area. Wetlands are often linked together by waterbirds and other animals that disperse plant seeds and spores between them, so the degradation of one area can have significant knock-on effects even for distant locations.

Read more:

Why a wetland might not be wet

Without concerted wetland conservation, individual conservation for species like the waterwheel plant become little more than band-aids.

For the waterwheel plant, a single isolated population in a remote and untouched corner of the North Kimberley could represent a crucial refuge. It gives a thin sliver of hope that this remarkable species will still exist for future generations to marvel at.

Waterwheel plants flourish in this oasis in the remote North Kimberley.

Adam Cross, Author provided

Conservation

Ecologists are working hard at conserving the waterwheel plant: monitoring habitats, reintroducing it into areas where it has become extinct and detailed study of its ecology and reproductive biology.

But ultimately, its future depends on the survival of wetlands – complex and sensitive ecosystems that can be affected by even small changes throughout their catchment area. Wetlands are often linked together by waterbirds and other animals that disperse plant seeds and spores between them, so the degradation of one area can have significant knock-on effects even for distant locations.

Read more:

Why a wetland might not be wet

Without concerted wetland conservation, individual conservation for species like the waterwheel plant become little more than band-aids.

For the waterwheel plant, a single isolated population in a remote and untouched corner of the North Kimberley could represent a crucial refuge. It gives a thin sliver of hope that this remarkable species will still exist for future generations to marvel at.

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.

Authors: Adam Cross, Research Fellow, Curtin University

Read more http://theconversation.com/the-waterwheel-plant-is-a-carnivorous-underwater-snap-trap-120424