a new book examines #MeToo in Australia

- Written by Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

Women have been sharing personal stories of sexual assault, abuse and harassment for – well – centuries. But in October 2017, when #MeToo went viral, there was a shift in the way these stories were received.

Suddenly, women were listened to with respect – that is, without the usual accompaniment of blame, insult, judgment and scepticism, followed by an unseemly rush to defend #NotAllMen.

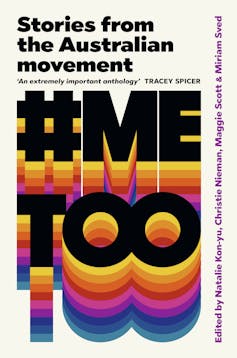

#MeToo: Stories from the Australian Movement is an anthology of Australian writing that explores this moment. Edited by Natalie Kon-yu, Christie Nieman, Maggie Scott and Miriam Sved, it includes the voices of 35 Australian women through essays, personal stories, pictures and even poetry.

#MeToo: a new anthology.

Picador

#MeToo: a new anthology.

Picador

It attempts to redraw the lines, in the words of the book’s editors, between sexual assault and other forms of behaviour: “The line between ‘a bit of fun’ and harassment.” It does so by refracting these behaviours through the “prism of women’s experiences”.

This is a brave book. It wades into all the difficult areas – veering between bad sex, humiliating youthful experiences, and things that are clearly wrong and criminal.

It tackles the toxic cultural practices that foster an environment in which gendered violence is more likely to occur – the dense web of attitudes that entrench unequal power relations, the treatment of women as objects, the rise of “rape culture”.

As Sarah Firth artfully points out in “Start Where You Are”, a gem of a graphic essay included in this anthology: the cry “smash the patriarchy” carries the unhelpful connotation that “patriarchy” is something that is easily identified and taken down. The accompanying illustration ironically features a character dreaming about taking an axe to a statue of a 17th century Cavalier, with a plaque helpfully labelled “MEN R #1”. Of course, it’s not that easy. This is why change is hard.

The problem of speaking out

In a standout opening essay, Kath Kenny writes about the difficulties faced by women who “choose” to speak out about sexual harassment. She deftly critiques the media’s requirement that each woman speak individually as a victim – and only as a victim.

As Kenny points out, in a world in which women make up less than a quarter of media subjects interviewed or reported on, often featuring as victims when they do, being positioned as a victim means that you’ll never be consulted as an “expert”. And that carries a real cost.

Individualised stories can be dismissed as anomalies, extremes and aberrations. They fail to threaten the social structures that allow abuse to continue. These stories, Kenny argues, “only get us so far”.

Read more: #MeToo has changed the media landscape, but in Australia there is still much to be done

Even where women choose not to speak publicly, they can still be made to “pay”. Take, for example, journalist Ashleigh Raper, who alleged that then-NSW Opposition Leader Luke Foley put his hands inside her underpants at a function in 2016. Raper chose not to make a complaint, but when the matter was raised in NSW parliament, the story became subject to intense media scrutiny – it was no longer her own.

Actress Eryn Jean Norvill made a private complaint against Geoffrey Rush to the Sydney Theatre Company, but allegations of his inappropriate behaviour were published by the Daily Telegraph without her involvement. Kenny writes that both women were “outed, mercilessly vilified and accused of inventing malicious lies”.

What many well-publicised #MeToo cases in Australia have in common is that the men involved have sued or threatened to sue for defamation. It’s not much of a leap to conclude that the reputational interests of the cashed up and powerful are better protected by law than those alleging harassment.

This is the problem addressed by Alison Croggon in her “Backgrounder” on the Geoffrey Rush case, which focuses on the ways in which the legal action failed to expose the true nature of power relations in the already highly insecure theatrical profession.

These include, Croggon writes, “disempowering mechanisms of denial, such as the suggestion that harassment isn’t harassment … the notion that it wasn’t serious or that the victim invited it”. And, she adds, “We’ve seen all of these claims at work in the trial”.

Read more: Geoffrey Rush's victory in his defamation case could have a chilling effect on the #MeToo movement

The ‘double-bind’

This anthology includes outstanding contributions from women of colour. Shakira Hussein writes powerfully about the double-bind that confronts all women of colour who “campaign against sexism in our communities, only to find our words used to stigmatise our collective identity”.

Eugenia Flynn confronts the multiple oppressions that face Indigenous women. She writes, “misogyny and predatory sexual behaviour are all part of the intergenerational trauma passed down and cycled around Indigenous communities”. But when exposed to the “blinding whiteness of Australian media” the pain is made worse, endowed with what Flynn calls an “almost pornographic” quality.

What Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women need, writes Flynn, is “self-determined solutions to the violence created by colonisation”.

Elsewhere, Fleur McDonald paints a horrifying portrait of domestic violence in rural communities, Kerri Sackville takes a despairing look at mid-life dating, Ginger Gorman wades into the world of online misogyny, and Nicole Hayes writes about carving out space in the male dominated world of AFL.

Read more: Not everyone can say #MeToo and we need to tackle the causes of sexual violence

In yet another standout contribution, Greta Parry questions the way wives of men who are “outed” for sexual misconduct are asked to “somehow make amends” for the behaviour of their partners, and come to be defined by that conduct, in ways that men are not.

There’s an uncomfortable sense throughout the book that women will face repercussions for speaking out. Comments sections will undoubtedly fill with people who opine on why it’s difficult to distinguish rape from sex, who allege that a footballer’s career is more important than a young woman’s right to safety, or worry that feminists are trying to stamp out sex, flirting and lacy underwear.

But as “the backlash begins in earnest” speaking out remains necessary because, in the editors’ words, “We can’t rely on men to change the world”.

Authors: Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia