New creatives are remaking Canberra's city centre, but at a social cost

- Written by Richard Hu, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Design & Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra

The new economy and new technology are changing Canberra’s city centre, Walter Burley Griffin’s design legacy of 100 years ago. While the central area is becoming an innovation precinct and a dynamic place, it comes with a cost of social gentrification and unaffordability.

In Griffin’s design for Canberra, the city centre was planned to be a lively business centre with high-density retailing and commercial uses. The original idea included a citywide tram network supported by higher-density development along the corridors. City Hill was intended to be a heart for the city’s citizens.

Griffin’s vision was not truly fulfilled, however.

Read more: Friday essay: how to fix Parliament House - what about some neighbours?

The knowledge cluster effect

The new economy seems to provide an opportunity unforeseen by Griffin to revitalise the city centre.

Canberra is a knowledge city, despite its comparatively small population and employment sector. Knowledge is Canberra’s industry.

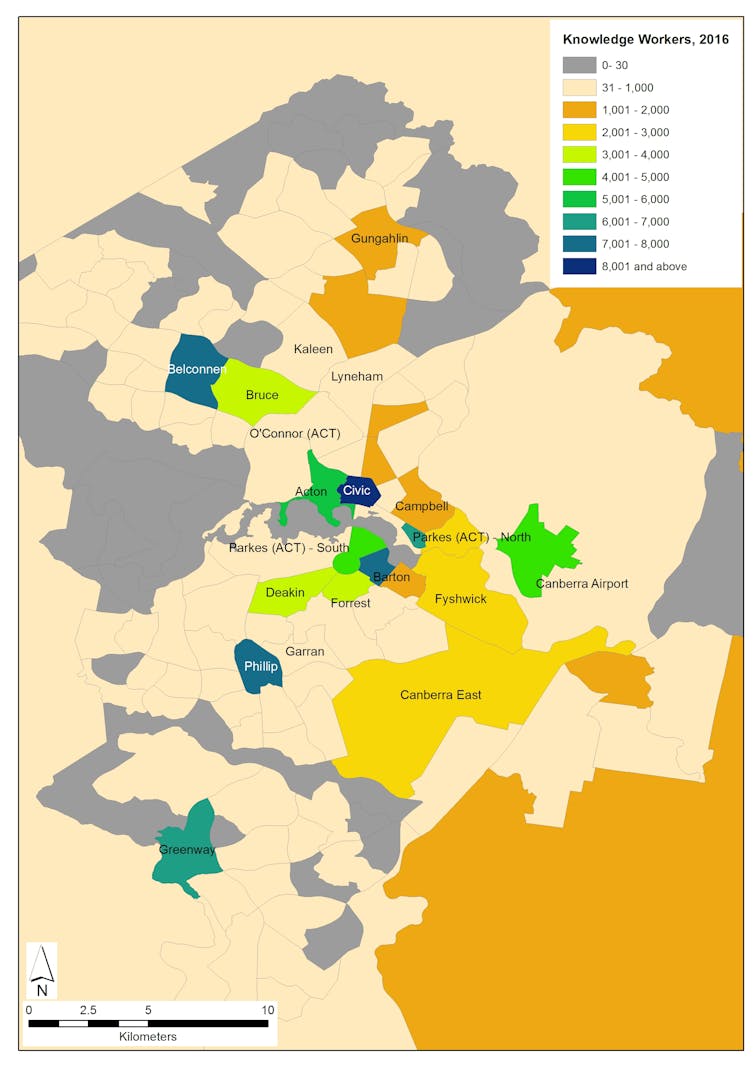

According to the Australian 2016 Census data, the city centre – known as the Civic – has the highest concentration of knowledge workers in the Canberra region (Figure 1). They are transforming the city centre’s functions, activities and spatial uses and pattern.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of knowledge workers in Canberra.

ABS 2016 Census

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of knowledge workers in Canberra.

ABS 2016 Census

Read more: The Knowledge City Index: Sydney takes top spot but Canberra punches above its weight

The transformation of city centres is a global phenomenon. It is happening in major Australian capital cities.

Canberra presents an extreme case to illustrate this point, as a planned city known for being a “bush capital” with suburban sprawl. The city of just over 400,000 people has an area of more than 800 square kilometres. But its compact centre is becoming more important in a globalised and networked society.

The city centre is more than a geographical or spatial centre. Its “centrality” is cultural, social, political and economical. Canberra’s city centre, a Modernist planning legacy, now exists in a setting of multiple global and local forces. These forces are intersecting with economic restructuring, ubiquitous information technology, knowledge diffusion and people movement.

As a result, the city centre is becoming more “centralised”: it is a cluster of functions, a magnet of activities.

The knowledge work and workers are reshaping the use of spaces and the public realm in the city centre. Innovation activities require more interaction and exchange, more access to public space and amenities, and more spatial and temporal flexibility. They are blurring the conventional division of land uses and space uses and challenging the old ways of design thinking.

One spatial impact of the new economy is the growing presence and practice of smart work in Canberra’s city centre. Creative workers are sharing spaces and facilities.

A smart work hub in Canberra city centre.

A smart work hub in Canberra city centre.

Creatives are moving in

In Canberra’s city centre, more well-designed and medium-density dwellings are being built and provided to meet the needs of the new creative workers who work and live there.

Population growth rate year ended March 31 2018.

ABS, CC BY

Population growth rate year ended March 31 2018.

ABS, CC BY

These creatives have impacts on both place and people. Canberra is growing fast, attracting people from interstate and internationally.

This growth includes large-scale movement of knowledge workers to the inner-city areas. The poorer socio-economic groups are being displaced from these areas.

People working as managers and professionals are moving into the increasingly desirable inner-city areas. As a result, rising housing and rental prices are pushing out existing inhabitants. According to Census 2016, nearly 1200 managers and professionals lived and worked in inner areas of Civic and Braddon, but only 170 technicians and labourers who worked there also lived there.

Urban renewal for everyone

While the precinct is becoming more dynamic and active, in contrast to people’s long-held (mis)perception of Canberra as a humdrum place, the change comes at a social cost. People on low incomes are dislocated and many young people, the most valuable capital for the city’s future, find the place increasingly unaffordable.

Thus, the very transformations that present opportunities for the city’s economic diversification and urban renewal also bring challenges in maintaining it as an equitable city.

Canberra’s urban renewal strategy should not embrace or celebrate the creative transformations only. It should also appropriately manage the social implications to genuinely make the city a place for everyone.

Read more: Canberra is 101 and Australia still hasn't grown up

Authors: Richard Hu, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Design & Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra