Warty hammer orchids are sexual deceivers

- Written by Ryan Phillips, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Environment & Evolution, La Trobe University

Orchids are famed for their beautiful and alluring flowers – and the great lengths to which people will go to experience them in the wild. Among Australian orchids, evocative names such as The Butterfly Orchid, The Queen of Sheeba, and Cleopatra’s Needles conjure up images of rare and beautiful flowers.

Yet there is a rich diversity of our orchids. Some are diminutive, warty, and unpleasant-smelling, bearing little resemblance to a typical flower.

Read more: 'The worst kind of pain you can imagine' – what it's like to be stung by a stinging tree

While many orchid enthusiasts have a soft spot for these quirky members of the Australian flora, what has brought them international recognition is their flair for using some of the most bizarre reproductive strategies on Earth.

The Conversation/Ryan Phillips/Suzi Bond., CC BY

Sexual mimicry

From the very beginnings of pollination research in Australia there were signs that something unusual was going on in the Australian orchid flora.

In the 1920s Edith Coleman from Victoria made the sensational discovery that the Australian tongue and bonnet orchids (Cryptostylis) were pollinated by males of a particular species of ichneumonid wasp attempting to mate with the flower.

But this was just the beginning.

The Conversation/Ryan Phillips/Suzi Bond., CC BY

Sexual mimicry

From the very beginnings of pollination research in Australia there were signs that something unusual was going on in the Australian orchid flora.

In the 1920s Edith Coleman from Victoria made the sensational discovery that the Australian tongue and bonnet orchids (Cryptostylis) were pollinated by males of a particular species of ichneumonid wasp attempting to mate with the flower.

But this was just the beginning.

The King-in-his-carriage, Drakaea glyptodon, is the most common species of hammer orchid. Here the flower is pictured next to the female of its pollinating thynnine wasp, Zaspilothynnus trilobatus.

Rod Peakall, Author provided

We now know that while the insect species involved may vary, many of our orchid species use this strategy. Australia is the world centre for sexual deception in plants.

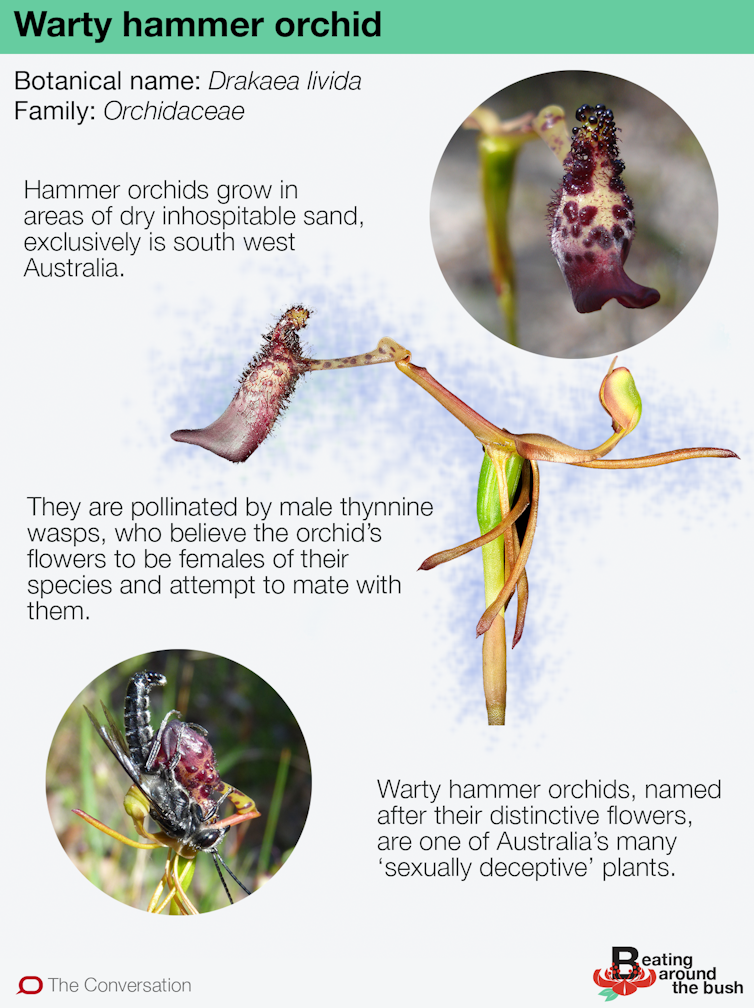

Perhaps the most sophisticated flower of all sexually deceptive plants is seen in the hammer orchids, a diminutive genus that only grows in southwestern Australia. Their solitary stem reaches a height of around 40cm, and each stem produces a single flower no more than 4cm in length.

Even among sexually deceptive orchids, hammer orchids stand out from the crowd. They have a single heart-shaped leaf that sits flush with the soil surface, and grow in areas of dry inhospitable sand – an unusual choice for an orchid.

The King-in-his-carriage, Drakaea glyptodon, is the most common species of hammer orchid. Here the flower is pictured next to the female of its pollinating thynnine wasp, Zaspilothynnus trilobatus.

Rod Peakall, Author provided

We now know that while the insect species involved may vary, many of our orchid species use this strategy. Australia is the world centre for sexual deception in plants.

Perhaps the most sophisticated flower of all sexually deceptive plants is seen in the hammer orchids, a diminutive genus that only grows in southwestern Australia. Their solitary stem reaches a height of around 40cm, and each stem produces a single flower no more than 4cm in length.

Even among sexually deceptive orchids, hammer orchids stand out from the crowd. They have a single heart-shaped leaf that sits flush with the soil surface, and grow in areas of dry inhospitable sand – an unusual choice for an orchid.

The thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus nigripes is a sexually deceived.

pollinator of the Warty hammer orchid. Here they are pictured in copula, with the

flightless female having been carried to a food source by the male.

Keith Smith, Author provided

And then there is the flower. Not only does the lip of the flower more closely resemble an insect than a petal, but it is hinged partway along. All of which starts to makes sense once you see the pollinators in action.

Like many other Australian sexually deceptive orchids, they are pollinated by thynnine wasps – a unique group in which the male picks up the flightless female and they mate in flight.

In the case of hammer orchids, the male grasps the insect-like lip and attempts to fly off with “her”. The combination of his momentum and the hinge mechanism swings him upside down and onto the orchid’s reproductive structures.

It’s not me, it’s you (you’re a flower)

So, how do you trick a wasp?

Accurate visual mimicry of the female insect does not appear to be essential, as there are some sexually deceptive orchids that are brightly coloured like a regular flower.

Instead, the key ingredient for attracting pollinators to the flower is mimicking the sex pheromone of the female insect. And boy, is this pheromone potent.

Indeed, one of the strangest fieldwork experiences I’ve had was wasps flying through my open car window while stopped at traffic lights, irresistibly drawn to make love to the hammer orchids sitting on the passenger seat!

The thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus nigripes is a sexually deceived.

pollinator of the Warty hammer orchid. Here they are pictured in copula, with the

flightless female having been carried to a food source by the male.

Keith Smith, Author provided

And then there is the flower. Not only does the lip of the flower more closely resemble an insect than a petal, but it is hinged partway along. All of which starts to makes sense once you see the pollinators in action.

Like many other Australian sexually deceptive orchids, they are pollinated by thynnine wasps – a unique group in which the male picks up the flightless female and they mate in flight.

In the case of hammer orchids, the male grasps the insect-like lip and attempts to fly off with “her”. The combination of his momentum and the hinge mechanism swings him upside down and onto the orchid’s reproductive structures.

It’s not me, it’s you (you’re a flower)

So, how do you trick a wasp?

Accurate visual mimicry of the female insect does not appear to be essential, as there are some sexually deceptive orchids that are brightly coloured like a regular flower.

Instead, the key ingredient for attracting pollinators to the flower is mimicking the sex pheromone of the female insect. And boy, is this pheromone potent.

Indeed, one of the strangest fieldwork experiences I’ve had was wasps flying through my open car window while stopped at traffic lights, irresistibly drawn to make love to the hammer orchids sitting on the passenger seat!

Pollination of the Warty hammer orchid by a male of the thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus nigripes.

Suzi Bond, Author provided

While determining the chemicals responsible for attraction of sexually deceived pollinators is a laborious process, we now know that multiple classes of chemicals are involved, several of which were new to science or had no previously known function in plants.

What’s more, we are still discovering new and unexpected cases of sexual deception in orchids that don’t conform to the insect-like appearance of many sexually deceptive orchids.

A classic example is the case of the Warty hammer orchid and the Kings spider orchid – these two species have totally different-looking flowers, yet both are pollinated by the same wasp species through sexual deception.

While the ability to attract sexually excited males without closely resembling a female insect may partly explain the evolution of sexual deception, it does not explain the benefit of evolving this strategy in the first place.

A leading hypothesis for the evolution of sexual deception is that mate-seeking males be more efficient at finding orchid flowers than food-foraging pollinators – but this remains a work in progress.

Pollination of the Warty hammer orchid by a male of the thynnine wasp Zaspilothynnus nigripes.

Suzi Bond, Author provided

While determining the chemicals responsible for attraction of sexually deceived pollinators is a laborious process, we now know that multiple classes of chemicals are involved, several of which were new to science or had no previously known function in plants.

What’s more, we are still discovering new and unexpected cases of sexual deception in orchids that don’t conform to the insect-like appearance of many sexually deceptive orchids.

A classic example is the case of the Warty hammer orchid and the Kings spider orchid – these two species have totally different-looking flowers, yet both are pollinated by the same wasp species through sexual deception.

While the ability to attract sexually excited males without closely resembling a female insect may partly explain the evolution of sexual deception, it does not explain the benefit of evolving this strategy in the first place.

A leading hypothesis for the evolution of sexual deception is that mate-seeking males be more efficient at finding orchid flowers than food-foraging pollinators – but this remains a work in progress.

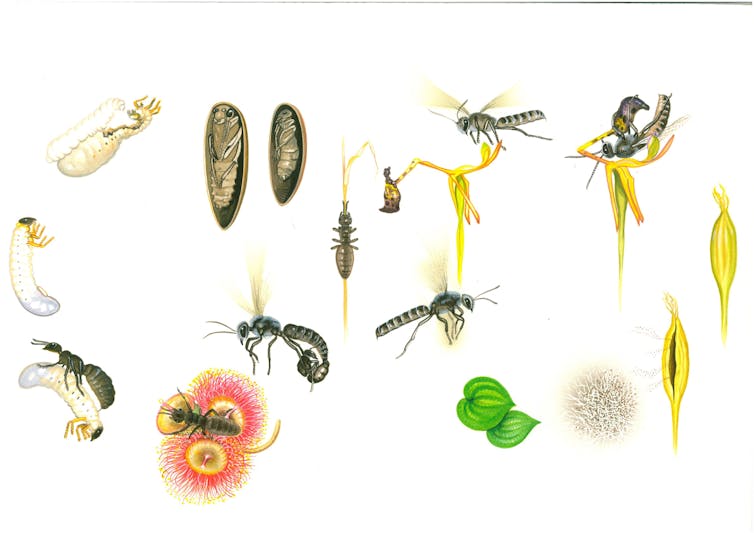

The life cycle of the Warty hammer orchid and its pollinator species,

highlighting the complex ecological requirements needed to support a population of.

the orchid.

Martin Thompson, Author provided

From a conservation point of view, pollination by sexual deception has some interesting challenges. Female animals produce sex pheromones that only attract males of their own species. This means an orchid that mimics a sex pheromone typically relies on a single pollinator species. As such, conservation of any given orchid species requires the presence of a viable population of a particular pollinator.

Further, an interesting quirk of these sexually deceptive systems is the potential for cryptic forms of the orchid: where populations of orchids that appear identical to human observers actually attract different pollinator species through shifts in pheromone chemistry. Indeed, of the ten known species of hammer orchid, three contain cryptic forms.

Read more:

Australia’s unusual species

Not only does this create a major challenge for managing rare species, it raises the possibility that – should these forms prove to be separate species – the true diversity of sexually deceptive orchids could be greatly underestimated.

The life cycle of the Warty hammer orchid and its pollinator species,

highlighting the complex ecological requirements needed to support a population of.

the orchid.

Martin Thompson, Author provided

From a conservation point of view, pollination by sexual deception has some interesting challenges. Female animals produce sex pheromones that only attract males of their own species. This means an orchid that mimics a sex pheromone typically relies on a single pollinator species. As such, conservation of any given orchid species requires the presence of a viable population of a particular pollinator.

Further, an interesting quirk of these sexually deceptive systems is the potential for cryptic forms of the orchid: where populations of orchids that appear identical to human observers actually attract different pollinator species through shifts in pheromone chemistry. Indeed, of the ten known species of hammer orchid, three contain cryptic forms.

Read more:

Australia’s unusual species

Not only does this create a major challenge for managing rare species, it raises the possibility that – should these forms prove to be separate species – the true diversity of sexually deceptive orchids could be greatly underestimated.

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.

Sign up to Beating Around the Bush, a series that profiles native plants: part gardening column, part dispatches from country, entirely Australian.

Authors: Ryan Phillips, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Environment & Evolution, La Trobe University

Read more http://theconversation.com/warty-hammer-orchids-are-sexual-deceivers-107805