Why we should remember Boorong, Bennelong's third wife, who is buried beside him

- Written by Meredith Lake, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney

More than 200 years after Woollarawarre Bennelong’s death, the NSW government has purchased the land where he is buried. On the north side of the Parramatta river, the unmarked grave site will be turned into a memorial to the great Wangal leader.

But Bennelong is not the only person interred at the spot. Boorong, his third wife, lies alongside him. She has intrigued me for years, since I first began researching the role of Christianity in the encounter between Eora and Europeans. She is not famous like Bennelong, or his second wife Barangaroo. So who was Boorong? And why should we remember her too?

Read more: Indigenous lives, the 'cult of forgetfulness' and the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Colonial sources only give us a few glimpses of Boorong. She is discussed briefly in letters by the first chaplain, Richard Johnson, and his wife Mary, with whom she lived for about 18 months in 1789-90.

Other first fleet officers and a few later colonists also mention her in their journals, using a range of names including Abaroo, Araboo, Aboren and Aborough – as well as Booron or Booroong. These mainly incidental references are coloured by the Europeans’ perspectives and agendas. There are no surviving records produced by Boorong herself - no equivalent to Bennelong’s letter.

Still, pieced together, these fragments suggest Boorong played a significant role in the initial interaction between black and white Australians. She was the first Indigenous person to have a substantial encounter with Christianity and its Bible. She was also a political go-between, a cross-cultural broker, and a survivor.

Boorong’s background

Boorong was the daughter of Maugoran, a Burrumattagal elder, and Goorooberra, whose name means “firestick”. She belonged to the Parramatta area, “the place where eels lie down”. Born there in the mid-1770s, she was about 12 when European colonists arrived.

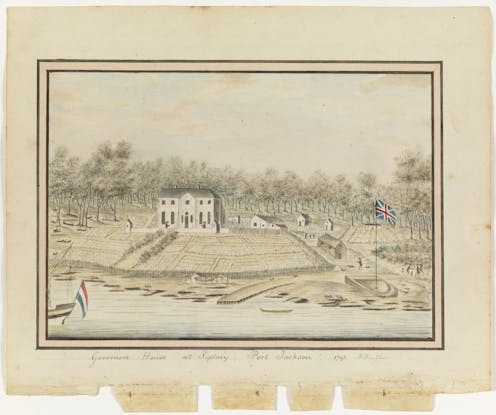

Boorong caught smallpox during the epidemic of autumn 1789. Some of Governor Phillip’s men found her sick and brought her into their camp for attention. She was nursed by Arabanoo, an Eora captive at Government House. Arabanoo caught the disease and died – along with as many as half the local Eora, including Bennelong’s first wife, whose name is lost to history.

Read more: Four Thousand Fish and Broken Glass connect Sydney's Aboriginal past to its present

Boorong, like Bennelong, was one of the survivors. According to Lieutenant Watkin Tench, she was then “received as an inmate, with great kindness, in the family of Mrs Johnson, the clergyman’s wife”.

We don’t know what Boorong thought of the Johnsons, what her agenda was, or how free she felt to stay or leave their hut. But Richard and Mary encouraged her to wear clothes, to speak English and to make herself useful around the house. The clergyman – an evangelical – taught Boorong the Lord’s Prayer and tried to convey an idea of “a supreme being”. His hope, he wrote to a friend, was to see “these poor heathen brought to the Knowledge of Christianity”.

The Reverend Johnson also “took pains” to instruct Boorong in reading, presumably using the Bible as a text for lessons. She thus encountered a new language, a new kind of literacy, and the technology of books and writing. These language skills meant she later got caught up in the political negotiations between black and white.

Early Sydney politics

By 1789, Governor Phillip had made virtually no progress in understanding the Eora - and had resorted to kidnapping people to establish a channel of communication with the local tribes.

After Arabanoo’s death, Phillip’s officers took in two more warriors by force. Coleby soon escaped his shackles, but Bennelong stayed longer - gathering information about the colonists and forging strategic relationships with Phillip and others around Government House. But then Bennelong, too, escaped – dashing English hopes that he would broker some kind of understanding between the two sides.

Read more: Rediscovered: the Aboriginal names for ten Melbourne suburbs

In this context, Phillip’s officers turned to Boorong, as well as a boy Nanberry, to act as go-betweens. On and off, between May 1789 and November 1790, they reluctantly relied on her as a translator and mediator with the Sydney tribes.

Boorong translated when Johnson and Lieutenant William Dawes went to find out who had speared Phillip at Manly Cove in September 1790.

Boorong also accompanied the officers on several visits to Bennelong during the spring of 1790, and conveyed their repeated requests that he come back to the British camp.

In late October, Bennelong indicated a willingness to go and visit Phillip. Barangaroo, Bennelong’s wife at the time, opposed the trip so strenuously that the officers offered a guarantee of safety: “Mr Johnson, attended by Abaroo (i.e. Boorong), agreed to remain as a hostage until Baneelon should return”.

Boorong rejects white society

There was a rapproachment of sorts between Bennelong and Phillip. And by late summer 1791, numbers of Eora were routinely staying in the town. The Rev. Johnson thought this new state of affairs had been “principally brought about” by Boorong, the “little girl” he had taught.

Boorong herself did not stay in the English camp. In October 1790, she returned to the bush neither converted to Christianity nor convinced of the colonists’ way of life. She continued to visit the Johnsons occasionally for at least five years after that, but in Mary Johnson’s words she did so “quite naked” and “evidently preferred [her] own way of life”. An image of Boorong, now held by the Natural History Museum in London, depicts her at her brother Ballooderry’s funeral in December 1791.

By 1797, Boorong was married to Bennelong. Barangaroo had died a few years previously, and Bennelong had survived a round trip to England. Boorong and Bennelong lived together with a band of perhaps 100 Eora survivors on the north side of the Parramatta river.

Around 1803 they had a son, known as Dickey, who as a young adult converted to Christianity, received baptism, and became probably the first Indigenous Australian evangelist.

We do not know the details of Boorong’s death, sometime around 1813. But in 1815, an Aboriginal elder known as “Old Philip” told ship’s surgeon Joseph Arnold that Bennelong had “died after a short illness about two years ago, & that they buried him & his wife at Kissing Point”.

In 1821 Nanberry, by his own request, was also buried alongside Bennelong – but that’s another story. In the meantime, let’s not memorialise Bennelong in a way that erases Boorong and her contributions as a negotiator and survivor.

Authors: Meredith Lake, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney