Niki Savva’s Earthquake is a damning account of the election that shook Australia

- Written by Mark Kenny, Professor, Australian Studies Institute, Australian National University

As federal polling day neared on May 3 2025, the ground was silent but the people of Australia stirred, some restless with fear, others hankering for a change of government. History favoured the incumbent. There had been no single-term governments nationally since the interwar years.

Deep in the bedrock of Australia’s political establishment, forces were building.

In 2022, despite his poor campaign, Anthony Albanese had been preferred, narrowly, by voters desperate to see the back of a dishonest Coalition government. He secured a very low primary vote (32.6%) and a majority of just two seats. A repeat of that uncertainty, as a sitting prime minister, might be politically fatal.

On paper, it could be close again, given the variables: a tremulous government out-argued in its 2023 Voice referendum; polling inaccuracies in several recent elections, which had under-measured outsider resentment; and a hard-charging opponent in Peter Dutton, leading a united team energised by his referendum success.

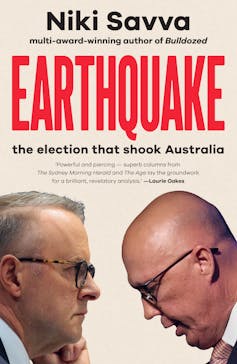

Review: Earthquake: The Election that Shook Australia – Niki Savva (Scribe)

In the end, this would be an election like no other and it would deliver a result like no other.

As the days counted down, it became clear that “Team Dutton” was running on little more than bloke-energy, a risky and unaffordable nuclear power policy and, crazily, higher taxes.

Albanese began well and became more assured as things progressed, despite an unusually large percentage of undecided voters. Labor’s campaign was measured and methodical. Its household-focused promises – such as an $8.5 billion Medicare boost – were iterative rather than novel, but at least well calibrated and thoroughly explained.

When the results came in, the electoral earth moved, all but banishing the Liberal Party from metropolitan Australia and eliminating Dutton from parliament.

Identity crisis

In her keenly anticipated new book, Earthquake: The Election that Shook Australia, veteran journalist Niki Savva charts the journey to an election result that caught everyone by surprise. But Earthquake is also a journey to the dead heart of the centre-right’s Trump-addled identity crisis.

In hindsight, the opposition’s failure was obvious. “By the time of the election, people knew what the Liberals opposed,” writes Savva:

What they couldn’t tell anymore was what they were for – or, if they could, they could no longer stomach it. The Liberal Party simply did not look, think, speak or act like modern mainstream Australia.

This damning critique grinds and yields like the San Andreas Fault under Savva’s savage, learned commentary. Perhaps more than any single promise or tactical error, it explains the career-ending, terrain-altering outcome.

Some readers may be inclined to skip the first half of the book, which begins with Savva’s newspaper columns. It is not until page 219 that Earthquake really starts in with its detailed retrospective analysis of the separate election campaigns and their stunning denouement.

These shorter essays nevertheless make the book at least partly contemporaneous and not merely the wisdom of 20-20 hindsight. They display the author’s well-trained instinct for political artifice and her contempt for instances of outright shape-shifting. Savva wrote of Dutton in mid-April, just weeks before the poll:

First, he was against working from home, then he wasn’t. First, he wanted a series of referendums, then he didn’t. First, he was gushingly pro-Trump, then he wasn’t.

And, as the saying goes, there’s plenty more where that came from.

On message, off target

The Liberal Party failed on just about every level, from its choice of leader, to its unquestioning acceptance of his bizarre suburban strategy – which involved surrendering the cities to the Labor-Teal-Green competition – to its vapid campaign, which was longer on indignation than hope for a nation.

As Savva says, the voters always get it right.

A key insight is the extent to which Dutton’s reclusive personality and the fecklessness of his front bench combined to leave nobody of sufficient weight and neutrality in charge of strategy.

Where Labor’s Paul Erickson worked closely with Albanese and his office to coordinate policy announcements, advertising, visits and debates, too many senior Liberals deferred to their leader, deluded, just as he was, by the outcome of the Voice referendum in 2023. Under this licence, Dutton made bad calls on tax policy, nuclear power stations and defence spending, allowing himself to be repeatedly outpositioned by Albanese.

As the respected Liberal Party grandee Nick Minchin notes in Earthquake, “you must never let the leader run the campaign”.

Meanwhile, Savva notes, Dutton kept up his habit of talking to conservative-friendly media, such as talkback hosts and Sky After Dark, where the conversations too often dragged him onto peripheral ground where there were no undecided voters to convince.

Niki Savva.

Scribe

Niki Savva.

Scribe

Even when he was on message, Dutton was off target. He hammered away at his temporary fuel excise cut, the nightly petrol station pictures reinforcing his men-in-trucks vibe, while Labor talked about affordable early childhood education, cheaper medicines and bulk billing.

Constantly surrendering the initiative is a strange way to run from behind, yet that is what Dutton set out to do. Core policy announcements were left too late, attracting negative attention for their absence, rather than positive coverage for any merits they might have had.

Labor’s campaigning approach was comparatively dynamic, even when the election had to be delayed due to Cyclone Alfred bearing down on the Queensland coast and, crucially, on Dutton’s own marginal seat.

The delay benefited Labor, notes Savva, because the expectation of an April poll had already brought additional scrutiny on Dutton. Thus, when he was found to have “skipped off to Sydney for a fundraiser”, it not only revived memories of Scott Morrison’s Hawaiian holiday in 2019, but gave Labor a devastating line that the Liberal leader had “sold out his constituents” by leaving his Dickson electorate at a moment of crisis.

“He was filling Liberal Party money bags while his own community was filling sandbags,” Labor’s then minister for agriculture Murray Watt charged on Insiders.

Both sides of the fence

Earthquake is an important account, featuring insights from a wide range of parliamentary and campaign insiders on both sides of the fence.

In its long-form journalism – telling the story via key players on the record – and its accounts of human failings under extreme pressure, it is a crucial adjunct to the political science from the Australian Election Study and other analytical work by psephologists.

Will the election result inform future actions? Given current behaviour, it seems the only people who weren’t rocked by the earthquake were the remnant Coalition MPs. Indeed, any remedial transformation of the federal party in its wake might be described as a work in regress.

Already, the Liberals have disavowed their Morrison-era commitment to net-zero by 2050, rejected quotas for women, doubled down on nuclear energy (as a way of claiming continued support of emissions reduction), and flagged migration cuts as a priority, despite the risk of further alienating migrant cohorts.

Earthquake, though, should be read as a cautionary tale for both sides. Their concrete silos stand half-empty; their grains of truth are no longer a staple in a world of fluid allegiances and ephemera.

A Labor meltdown cannot be ruled out, nor the corrosive effects of the hubris evident in the government’s defiance of the transparency and accountability it promised. It is possible the next election will bring a return to orthodoxy, with the Liberals recovering support in inner-city seats. Possible, though that would require another tectonic shift.

Authors: Mark Kenny, Professor, Australian Studies Institute, Australian National University