New report reveals glaring gaps between Australia’s future needs and science capabilities

- Written by Chennupati Jagadish, President of the Australian Academy of Science and Emeritus Professor of Physics and Electronic Materials Engineering, Australian National University

Since 1945, three-quarters of all global economic growth has been driven by technological advances. Since 1990, 90% of that advance has been rooted in fundamental science, according to Michael M. Crow, president of Arizona State University.

Corporate leaders in the United States understood this decades ago when they urged Congress to back “patient capital” for research – because this type of investment creates openings for breakthrough applications.

Think of the building blocks of our modern economy – wifi, smartphones, advanced cancer therapies, drought-tolerant crops and satellite navigation. These began as basic research, often with no obvious immediate application. Then they became the platforms for whole new industries.

But in Australia, we still treat research funding as a discretionary extra, subject to the ebb and flow of political expediency and annual budgets. Despite decades of speeches, reviews and strategic papers, our investment in knowledge creation and its application has nose-dived.

Today, the Australian Academy of Science released a landmark report that systematically measures our science capability against future needs for the first time.

The findings are blunt. We have gaps – in workforce, infrastructure and coordination – that will cripple our ability to secure a bright future for the next generation, unless we act now.

What did the report find?

The new report maps Australia’s scientific capability and shortfalls across three major areas.

Over the next decade, Australia is facing a demographic change with an ageing population, a decreasing fertility rate, and increasing growth in urban and regional cities.

The second national challenge is technological transformation. In most areas of life, we’re experiencing rapid technological changes. This includes advances in artificial intelligence (AI) that are already changing the shape of the workforce.

The third challenge is climate change, decarbonisation and environment. It’s imperative for Australia to transition to a net-zero economy and become resilient against the impacts of climate change.

What do we need to have in place for Australia to meet these challenges by 2035? Two key factors are science literacy and education, and national resilience. In a world of fractured geopolitics and technological competition, the countries that will thrive are those that can generate and apply knowledge for their own needs, in their own context.

The report has found eight key science areas that will be most in demand by 2035: agricultural science, AI, biotechnology, climate science, data science, epidemiology, geoscience and materials science.

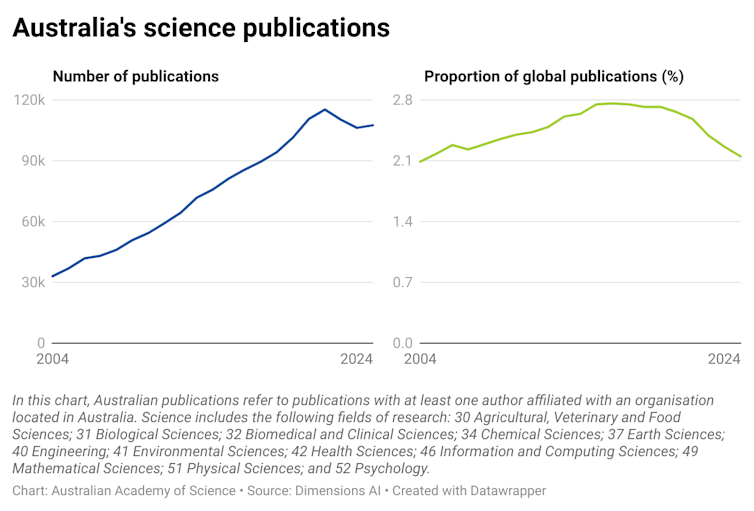

For each of these, the report contains a full dashboard that shows gaps in capabilities – from education to workforce needs, research and development spending, publications and more.