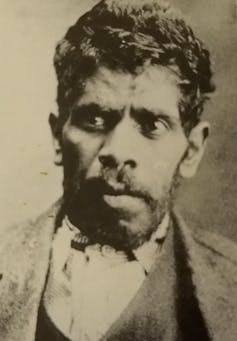

Black bushranger brothers Jimmy and Joe Governor were hanged in 1901. But were they ‘wicked’ or wronged?

- Written by Tim Rowse, Emeritus Professor, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

The homicidal actions, flight, capture, trial and punishment of Jimmy and Joe Governor (and their accomplice Jack Underwood) in 1900 are relatively well known. They were immortalised in Thomas Keneally’s historical novel, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1972) and the 1978 film version by Fred Schepisi.

In the winter of 1900, Jack Underwood and the Governors murdered nine people – men, women and children – across New South Wales. Jack was quickly captured and tried, while the Governor brothers evaded a manhunt for months, calling themselves “bushrangers”. Settlers fatally shot Joe; Jimmy was wounded, captured and tried. Jack and Jimmy were hanged in January 1901, within weeks of Australia becoming a new nation.

Review: The Last Outlaws: the crimes of Jimmie and Joe Governor and the birth of modern Australia – Katherine Biber (Scribner)

What can Katherine Biber, a historian of legal institutions, bring to a retelling of this sorry tale?

Biber is a critical historian of the law as an instrument of colonisation. The Governor brothers were labelled “half-castes” in the racial terminology of those times, but called Wiradjuri/Wonnarua in Biber’s telling; Underwood was their friend and work mate. Biber invites us to see their “lives, crimes and deaths” in the context of “bigger national ambitions: sovereignty, policing, surveillance, bureaucracy and the rule of law”.

With that macro-history in mind, Biber offers two visions of New South Wales in 1900.

Jimmy Governor was immortalised in the 1970s novel and film, The Chant of Jimmie Backsmith.A modern society and capitalist colony

In the first vision, the legal system is treated as an impersonal system of connected roles performed under the rule of law: policeman, coroner, judge, prosecutor, hangman. While the rule of law is no mere sham, Biber never lets us forget the humanity of those who staffed it and made it work.

She contextualises each man’s “office” in his individualised social history. For example, when Joe Governor was fleeing his crime, he was stalked and killed by the Wilkinson brothers – so, by law, there had to be an inquest. The coroner appointed to do this was Harry Pinchin, “a civilian who ran a shoe and boot business, and a cordial factory”. The letterhead Pinchin used in his coronial duties documented that he was a real estate agent, too. So his “civic duties” were among his “remunerated side hustles”.

In deft sketches like this – and there are many – Biber reminds us any impersonal system has to be staffed by people. These officials were also men on the make, some more competent and conscientious than others in carrying out their duties.

Biber makes much of the bureaucracy’s internal debates and inquisitions. Officials watched over one another to ensure they behaved appropriately – including on the proper disposal of Joe Governor’s brain, an object of interest to science. Biber is alert to the variety of ways one could be a “colonial” Australian. She writes: “local police attitudes towards Aboriginal peoples, and their responsibilities for them, reflected the full spectrum of humanity, from genocidal monsters to sincere amity”.

By paying attention to the personal dynamics and professional norms within the state apparatus, Biber presents New South Wales as not only a system of offices and duties but also, in the second element of her vision, as a class-ridden British settler colony, founded on the dispossession of native peoples.

Through the efforts, primarily of lawyers, this colony was about to federate with five other similarly constituted British colonies. Biber’s splendid aphorism reads: “Federation was to tie nationalist ribbons on colonial tethers.”

Telling the Governor and Underwood story becomes a way for Biber to show a society responding to their crimes as an orderly and modern bureaucracy, as a capitalist colony and as a nascent nation.

That Australia became a nation in the same month its oldest colony executed two “black” outlaws is a coincidence that gave rise to a joke: the Sydney Sportsman‘s announcement that authorities had decided not to execute Jimmy Governor until they had “sobered up sufficiently to enjoy the hanging”.

For Biber, the coincidence of federation and execution makes the Governor/Underwood story an allegory for the nation. The institutions of justice that properly processed the Black men’s crimes were also reproducing a social order that was in denial about its own fundamental injustice. “The entire saga illuminates the centrality of land theft in the narrative of Australian politics, law and public administration,” she writes.

Ferocious cruelty

Biber could have gilded this indictment by downplaying the awful fact that, between them, Underwood and the Governor brothers killed nine people (mostly women and children) and injured and robbed others. It began with the murder of Grace Mawbey, who employed Jimmy Governor’s wife, three of her children Grace (16), Percival (14) and Hilda Mawbey (11), and a school teacher, Helen Josephine Kerz. Biber makes sure, early in the book, that chopped and bashed bodies confront any reader tempted to frame the murderers sympathetically, as victims of colonisation.

Not only does she want us not to forget these men’s ferocious cruelty, but her description of the first crime scene – the Mawbey homestead – serves to introduce an office vital to her story: the coroner. In the first instance, this was R.G. Dalhunty, who came from Dubbo in July 1900 to record “blood, hair and brains” of women and children “scattered about the floor” of the Mawbey home.

To imagine having to find words for this scene is to experience both visceral and moral disgust. A society progressing by making and administering law was understandably outraged and terrified, reading what these men had done to the women and children of the Mawbey household.

However, the very existence of such words in a coronial document also assures readers (then and now) that there was (is) a system – governed by law – for dealing with extreme violence. Here, horrors are objectively recorded, by a person authorised to do so, enabling the legal process to take its course.

Jack Underwood was captured soon after the Mawbey massacre, but the Governor brothers – elusive for three months – triggered an unusual legal manoeuvre. On October 5 1900, New South Wales declared the Governor brothers “outlaws” under the Felons Apprehension Act 1899. Explaining the significance of this step, Biber’s familiarity with the history of the law does the reader a service.

How could the trial have been different?

Declaring the Governor brothers outlaws made it legal for the Wilkinson brothers to shoot Joe Governor on October 30. However, once Jimmy was captured and in the dock, his “outlaw” status presented a possible legal obstacle to his conviction.

His defence counsel, Frances Boyce, argued the trial should not proceed, as the state – by declaring him an outlaw – had already convicted him. This argument carried the risk that, if the court agreed, Jimmy Governor could immediately be executed, as a justifiable sequel to his conviction.

The prosecutor, Charles Wade, argued the Felons Apprehension Act merely expanded police and public powers to arrest a felon. Once in custody, Wade insisted, the arrested person was entitled to be tried before the judge issued any sentence.

The jury agreed with Wade. So, after a new jury was empanelled, Jimmy Governor was tried. He was found guilty of murdering teacher Helena Kerz.

In one strand of Aboriginal oral tradition, the Governor brothers were “bad blackfellows” who alarmed their contemporaries, Black and white. One newspaper’s account of Aboriginal views included the terms “scoundrel” and “wicked man”.

This does not stop Jimmy’s great-granddaughter, Aunty Loretta Parsley, and other descendants acknowledging him now as an ancestor. He has a place in Aunty Loretta’s family tree, which is unfurled for Biber’s inspection. Aunty Loretta is glad, she tells her, that Jimmy’s death mask is in the care of the National Museum of Australia, under restricted access.

The trial evidence points to the Governor brothers being provoked to murder by racist taunts. It includes testimony from not only Jimmy, but also his (white) wife Ethel. Mrs Mawbey and Miss Kerz had scorned her for throwing herself away on a blackfellow. “Ethel’s treatment was his motive” for murdering Miss Kerz, Biber suggests.

A jury might have been persuaded by the defence lawyer to see Jimmy as retaliating to severe provocation – with no intention to kill. Such a construction of Jimmy’s mind would have enabled a manslaughter conviction.

In Aunty Loretta’s view, a more competent lawyer would have saved Jimmy from execution. Biber believes that the (all-white) jury lacked empathy for a man so humiliated.

Did it shape modern Australia?

Was the prosecution of Jimmy Governor “a key event shaping modern Australia”? “Shaping” suggests causation: Biber is suggesting the state’s response to the deeds of Underwood and the Governor brothers contributed to the “modernity” that interests her most. That is, Aboriginal “protection”.