a reinvention of self – the pleasure of literary journeys

- Written by Edwina Preston, PhD Candidate, Creative Writing, The University of Melbourne

In the hiatus that was COVID lockdown, the novelty of “staying put” had a peculiar grace and delight. To limit one’s trajectory to five kilometres meant homing in on the small and the local: the seasonal repetitions of a plant blossoming in a neighbour’s garden, new pale green leaves on trees, a smell of liquorice in the air heralding summer. I looked closer at the local and saw new things, or perhaps I saw old things with new eyes.

But with the reopening of airports – even in the face of inflated fares – I was planning my escape routes immediately. Carbon footprint aside: since COVID, I have been to France twice, to Italy, to Spain, to England, to Greece, to California, and to Indonesia, not to mention Adelaide, the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast.

I am gorging myself on travel, gluttonously, amassing memories and experiences, banking my travels like a spendthrift Scrooge. In the COVID era, travel became something to look forward to and look back on, an adventure put on hold. I now have a lust for experiencing what was, temporarily, forbidden and could conceivably be forbidden again. As much as I enjoyed discovering the charms of local wetlands, travel beckons with more allure than ever.

I began reading Literary Journeys – a compendium of what I will loosely call “travel novels” – the same day I went to hear Scottish historian William Dalrymple speak at the Palais theatre in Melbourne. I sat there in the Palais with my wine and popcorn and listened to Dalrymple talk, with contagious enthusiasm, of actual geographical journeys, but also of the intercontinental travel of ideas, stories, ways of being human – the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Buddhism and Hinduism.

Sated on the soft air of France, the crisp air of London, the sultry air of Indonesia, I could give myself up to imagined journeys. Air, I thought, is the medium of travel – moving through it, catching ideas on it.

If we can’t physically travel, stories of travel become our vicarious vessels. Reading is inherently transportive: a way of journeying on the wings of others without moving from the armchair (or, in my case, bed).

To read is to commune, from a place of solitude, with other readers who have entered the same imaginary terrain: to read a travel narrative is to walk (or drive or sail), in solitude, with other travellers whose steps have worn the path.

The pantheon

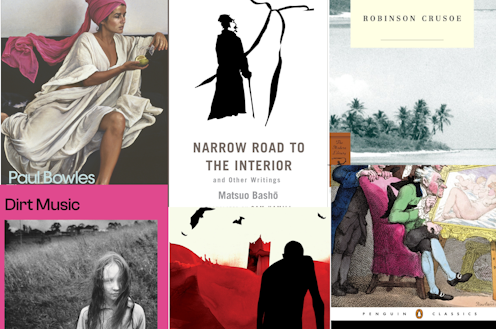

The editorial brief for Literary Journeys, required that all works selected for the book describe fictional journeys based on real locations. (There’s no Narnia here, no Middle Earth, no Phillip Pullman windows cut between worlds.) Literary Journeys is both a “travel companion” and “time machine”, chronologically arranged from 725 BCE to 2021, with several multi-century leaps; a chocolate-box sampler of travel fiction (albeit good chocolate with a high cocoa content and very little sugar).