If Australia was a small developing country, then the ability of the oil and gas industry to exploit our political system, and in turn our natural resources, would make perfect sense. Most people have read stories of multinational companies bending the domestic policies of developing countries to suit the interests of the fossil fuel industry.

Few people would believe that a country like Australia would fall for the same tricks. But as freelance journalist Royce Kurmelovs points out in his new book Slick: Australia’s Toxic Relationship with Big Oil, most people underestimate just how far in advance the fossil fuel industry plans not only its new projects, but its PR and lobbying efforts, as well.

Review: Slick: Australia’s Toxic Relationship with Big Oil – Royce Kurmelovs (University of Queensland Press)

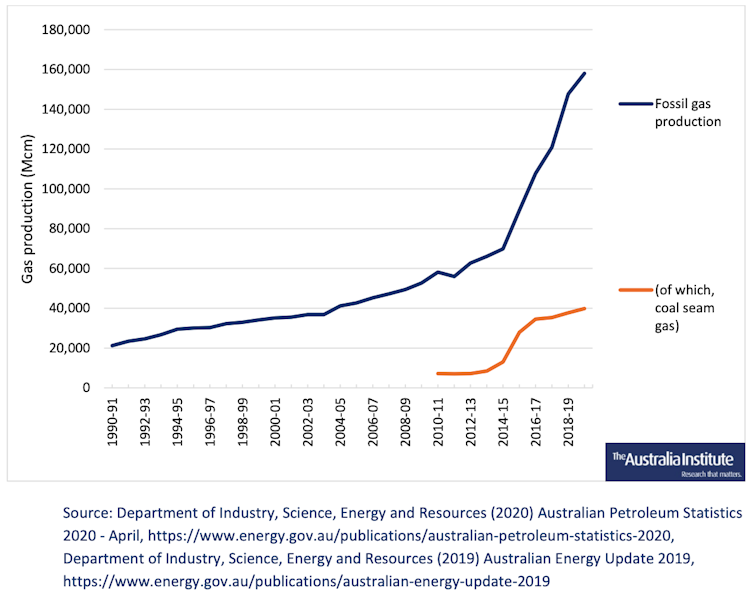

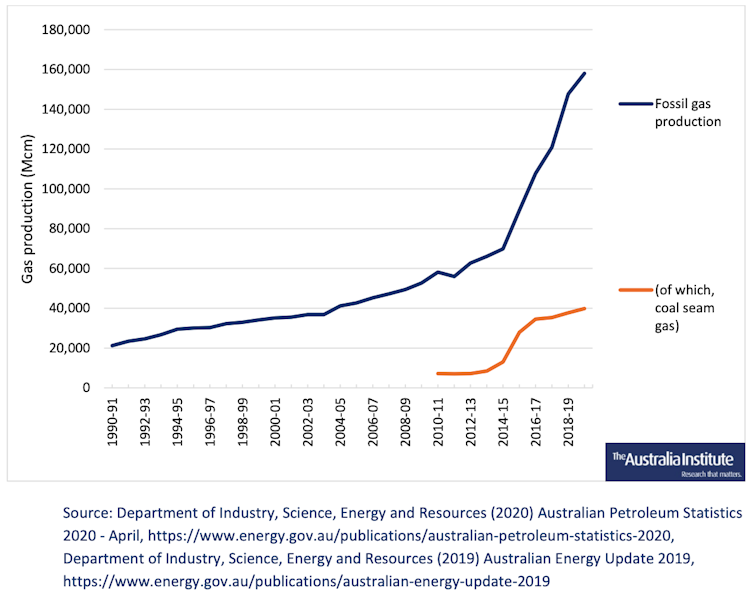

Australia is the world’s third-largest fossil fuel exporter. Our exports of liquified natural gas (LNG) are currently behind only Qatar and the United States. But what is most remarkable about the scale of Australia’s gas exports is how rapidly they have grown in recent years.

As Paris was planning to host the 2015 climate conference, at which the world would commit to limiting climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the oil industry was working on an ambitious plan to increase Australia’s gas exports by more than 300%, a plan it accomplished. From 1990 to 2010, Australian gas production tripled; from 2010 to 2019, it tripled again.

Fossil gas production in Australia, 1990-2019.

Tom Swann/Australia Institute.

Read more:

We pay billions to subsidise Australia’s fossil fuel industry. This makes absolutely no economic sense

Long-term plans

A real strength of Kurmelov’s writing is the way he engages the reader with the real world consequences of the climate change the fossil fuel industry has already caused, while exposing just how long, and how hard, the industry has had to work to cause that damage.

Many books about climate change are worthy but dull. Slick, however, is as readable as it is shocking. The book opens with a heartbreaking account of the Lismore floods of 2022. Kurmelovs then effortlessly steps the reader through the science, politics and economics of the oil industry’s long-term plans, always grounding these facts and their implications in human stories that resonate.

For me, a real strength of this book is its willingness to confront the role that the Australian public service has played in facilitating and enabling the rapid and subsidised expansion of the fossil fuel industry in Australia.

Much has been written about the lobbying efforts of the fossil fuel industry, but less has been written about who they were lobbying, and why their efforts were so successful.

It is easy, even comfortable, to blame gullible or greedy politicians for the fact that more than half the gas Australia exports is given away to the fossil fuel industry for free. But the fact is Australia has had eight resources ministers in the last ten years. It is hard to believe that a frank and fearless public service was unable to stand up to any of them.

For me, a real strength of this book is its willingness to confront the role that the Australian public service has played in facilitating and enabling the rapid and subsidised expansion of the fossil fuel industry in Australia.

Much has been written about the lobbying efforts of the fossil fuel industry, but less has been written about who they were lobbying, and why their efforts were so successful.

It is easy, even comfortable, to blame gullible or greedy politicians for the fact that more than half the gas Australia exports is given away to the fossil fuel industry for free. But the fact is Australia has had eight resources ministers in the last ten years. It is hard to believe that a frank and fearless public service was unable to stand up to any of them.

Minister for Resources Madeleine King speaking at the Australian Energy Producers Conference, Perth Convention and Exhibition Centre, May 21, 2024.

Richard Wainwright/AAP

Concealing the risks

I have written elsewhere about the longstanding focus of Australian governments on the risk to exports as other countries decide to use less fossil fuels. Slick goes back earlier still.

In a chapter titled Hot Air and the Cold Facts, Kurmelovs provides an engaging and illuminating account of the detective work he undertook to unearth the origins of Energy 2000, a policy document published by the Australian public service in 1988.

Even back then, our public service was working hard to downplay the risks of climate change, while protecting the interests of fossil fuel exporters. Kurmelovs includes the following quote from Energy 2000:

The so-called “greenhouse effect”, thought to be caused by increased carbon dioxide levels resulting from fossil-fuel combustion, will require consideration by government and industry. These problems have little effect on the domestic use of coal, but they could affect the use of and cost of using coal overseas, with consequent implications for our exports.

This is the earliest acknowledgement I have seen by Australian bureaucrats of the tension between the global need to tackle climate change and Australia’s desire to expand fossil fuel production.

Minister for Resources Madeleine King speaking at the Australian Energy Producers Conference, Perth Convention and Exhibition Centre, May 21, 2024.

Richard Wainwright/AAP

Concealing the risks

I have written elsewhere about the longstanding focus of Australian governments on the risk to exports as other countries decide to use less fossil fuels. Slick goes back earlier still.

In a chapter titled Hot Air and the Cold Facts, Kurmelovs provides an engaging and illuminating account of the detective work he undertook to unearth the origins of Energy 2000, a policy document published by the Australian public service in 1988.

Even back then, our public service was working hard to downplay the risks of climate change, while protecting the interests of fossil fuel exporters. Kurmelovs includes the following quote from Energy 2000:

The so-called “greenhouse effect”, thought to be caused by increased carbon dioxide levels resulting from fossil-fuel combustion, will require consideration by government and industry. These problems have little effect on the domestic use of coal, but they could affect the use of and cost of using coal overseas, with consequent implications for our exports.

This is the earliest acknowledgement I have seen by Australian bureaucrats of the tension between the global need to tackle climate change and Australia’s desire to expand fossil fuel production.

Royce Kurmelov.

University of Queensland Press

Kurmelov’s book is timely and important. It arrived just months after the current resources minister, Madeleine King, released the Albanese government’s Future Gas Strategy.

In launching that strategy for gas “to 2050 and beyond”, King published an article that argued “we will need more sources of gas”.

This was despite the fact that the UN secretary-general and the head of the International Energy Agency have made clear that if the world is to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees then we need to stop building new oil, gas and coal projects.

Australia is not a small developing country. Its governments and public servants are neither naive nor ignorant about the dangers of climate change and the role that fossil fuels play in causing it.

It is easy to believe that our leaders are focused on the short term, even though there is bipartisan support for A$368 billion worth of nuclear submarines that won’t be delivered for decades. But it takes effort and resolve for Australian policy makers to continue to subsidise and approve new fossil fuel projects, despite the strength of scientific and public opinion opposing them.

Slick helps Australians understand just how long, and how hard, the oil industry has worked to ensure that, whoever is in government in Australia, fossil fuel exports just keep growing. Hopefully, it will also encourage more Australians to do something about it.

Authors: Richard Denniss, Adjunct Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

Royce Kurmelov.

University of Queensland Press

Kurmelov’s book is timely and important. It arrived just months after the current resources minister, Madeleine King, released the Albanese government’s Future Gas Strategy.

In launching that strategy for gas “to 2050 and beyond”, King published an article that argued “we will need more sources of gas”.

This was despite the fact that the UN secretary-general and the head of the International Energy Agency have made clear that if the world is to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees then we need to stop building new oil, gas and coal projects.

Australia is not a small developing country. Its governments and public servants are neither naive nor ignorant about the dangers of climate change and the role that fossil fuels play in causing it.

It is easy to believe that our leaders are focused on the short term, even though there is bipartisan support for A$368 billion worth of nuclear submarines that won’t be delivered for decades. But it takes effort and resolve for Australian policy makers to continue to subsidise and approve new fossil fuel projects, despite the strength of scientific and public opinion opposing them.

Slick helps Australians understand just how long, and how hard, the oil industry has worked to ensure that, whoever is in government in Australia, fossil fuel exports just keep growing. Hopefully, it will also encourage more Australians to do something about it.

Authors: Richard Denniss, Adjunct Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National UniversityRead more