The stories of Australia’s Muslim Anzacs have long been forgotten. It’s time we honour them

- Written by Simon Wilmot, Senior Lecturer, Film, Deakin University

Among the many Australians who served during the second world war, there is a small group of people whose stories remain largely untold. These are the Muslim men and women who, while small in number, made significant contributions and sacrifices during the war effort.

Living in the time of the White Australia Policy, they were simultaneously wanted and rejected. Despite their sacrifices, many faced discrimination and even deportation upon their return.

Our ongoing research is looking into the lives of Australian-Muslim servicemen and women during WWII. In doing so, we have come across incredible stories of sacrifice and hardship that reveal not all war veterans were treated equally, nor are they all remembered the same.

The many faces of Islam in Australia

Australia’s Muslim Anzacs were a mix of Australian-born people and migrants. The Australian-born were the children and grandchildren of Afghan cameleers, Malay traders and Javanese labourers.

Several descendants of Afghan cameleers had Indigenous heritage, such as William “Billy” Bonsop of Mackay, who died in battle in New Guinea in 1943, and Akbar Namith Khan of Oodnadatta, who had active service in the Northern Territory.

Others were temporary immigrants who, when the war broke out, were unable to return home. When WWII began, many Albanian men were in Australia as part of the cultural practice of “kurbet”, where men would work abroad to earn money for their family.

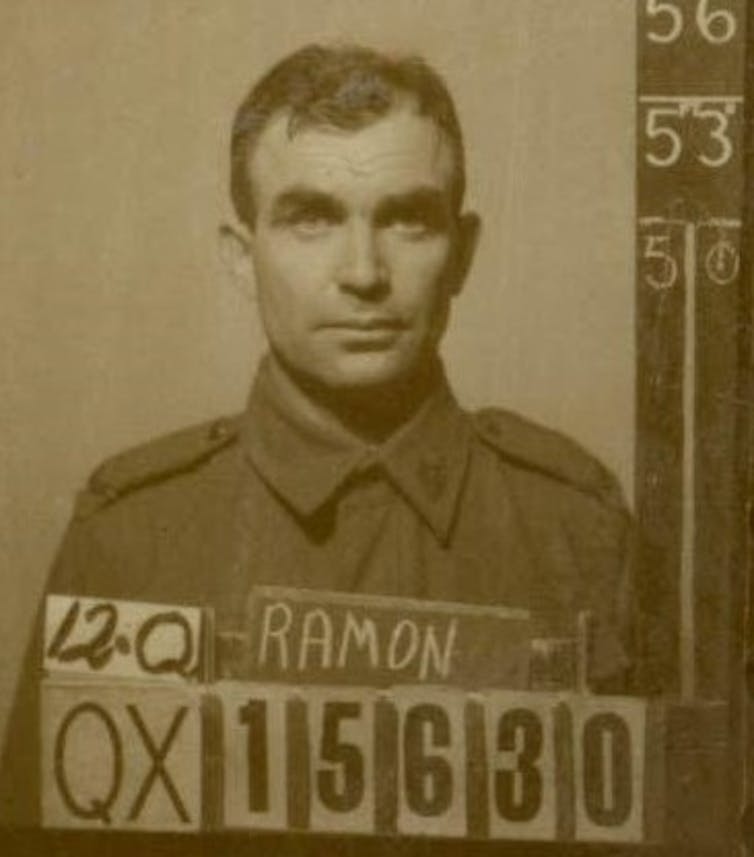

One of these Albanians was Kurtali Raman of Mareeba, North Queensland – a place where many Albanians went to work on tobacco farms. Raman joined the 2/31 Battalion and was among the first Australian soldiers to re-enter the village of Kokoda when it was taken back from the Japanese. He was killed in action at Papua on December 1 1942, at age 35.

Bravery, loss and betrayal

Another group of stranded workers were Indonesian and Malay indentured pearl divers. One man whose service exemplifies both the sacrifice and injustice of war was Malaysian-born Abu Kassim bin Marah.

Abu Kassim arrived in Broome as a teenager in 1933 to work in the pearling industry. At the outbreak of war, he was living with his long-term partner, Patricia Djiween, and their two daughters, Faye and Georgina. Patricia was Indigenous and, despite the family they had made, Western Australia’s “Protector of Aborigines” at the time (the government official appointed to oversee the welfare of Aboriginal people) denied them permission to marry.

Following the Japanese bombing of Broome in February 1942, Broome’s pearl divers were evacuated to Fremantle. The Malays and Indonesians were classified as “allied aliens” which meant they could enlist, which Abu Kassim did.

He was first assigned to a labour battalion where his seafaring skills were put to use in water transport. However, while serving the country, the government removed his two daughters from their mother’s care and placed them in an orphanage.

In 1944, the Z Special Unit, based in Australia recruited Abu Kassim and several other divers after failing to successfully insert white Australian soldiers behind enemy lines. The divers were promised naturalisation and an end to their indenture as incentives to join.

Their fitness, language skills and local knowledge of Southeast Asia proved invaluable. Abu Kassim trained at the Fraser Island Commando School and his unit chose him as one of the first to be deployed overseas as part of Operation Semut. In April 1945, Abu Kassim parachuted into Japanese-held Sarawak in Borneo.

Having first contacted friendly Kelabit villagers, Abu Kassim and his companions moved up the Rejang River, convincing local Iban and Kayan people – who had a history of enmity with one another – to put aside their differences and support the Australians. He recruited many local people to join their guerrilla force against the Japanese.

Abu Kassim then went ahead through the Japanese-held jungle to reach the coast, scouting enemy positions and gathering intelligence. He participated in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese, during which he was wounded in hand-to-hand combat.

He repatriated to Australia in December 1945. He was sick from his wounds and jungle illnesses, and soon discovered he had leukaemia. Upon his return, he applied for naturalisation but was rejected. As he was too sick to return to pearl diving, the government announced its intentions to deport him.

Abu Kassim was also unable to reunite with Patricia, since she was now married to a man named Snowy Dodson. But Abu Kassim gave his blessing for their union and for Dodson to look after his children. The two sisters would later be joined by two brothers, Patrick and Michael Pat and Mick Dodson went on to become prominent Aboriginal leaders, and a senator and barrister, respectively.

Abu Kassim‘s deportation orders were being processed when he died of leukaemia on March 3 1949. The veteran was buried in an unmarked grave in the Muslim section of Karrakatta Cemetery in Perth.

Only in 2021 was his grandson able to right some of the wrongs of his treatment and identify his grave so it could have a headstone.

Our documentary, Crescent Under the Southern Cross.Lest we forget

Despite the promise of rewards for their service, many of the other divers were held to the indentured labour agreements they had with pearling bosses.

The Albanians fared better. For them, war service became a pathway to naturalisation. Many of these men, such as Laver Xhemali and Mustafa “James” Sheriff, successfully had families and became important members of their communities. Laver Xhemali died in 1991 at age 70. His grave plaque is the first Australian War Memorial grave to feature the Islamic crescent.

At the same time, many Australian-born Muslim servicemen returned to face the same discrimination they endured before the war, and their service faded into obscurity.

Authors: Simon Wilmot, Senior Lecturer, Film, Deakin University