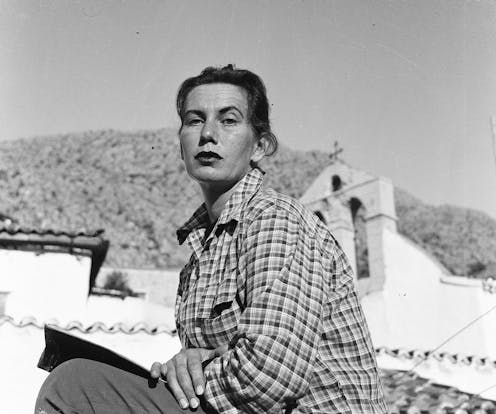

Charmian Clift’s taut, intimate, unfinished novel feels like a slightly broken book

- Written by Paul Genoni, Associate Professor, School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry, Curtin University

The publication of The End of the Morning is a long-awaited moment in Australian literature.

Readers familiar with Charmian Clift will be aware this book’s protagonist, Cressida Morley, is the writer’s alter-ego. Morley was to have been the vehicle for Clift’s self-representation in an autobiographical novel she was working on for some years prior to her death in 1969.

The End of the Morning – Charmian Clift, edited by Nadia Wheatley (NewSouth)

The End of the Morning marks the arrival of Morley, as seen through her own eyes and represented in her own words.

Clift’s suicide has been explained, in part, as the result of her inability to make progress on the novel that was to bring Morley to life. It was to be the tale of a Kiama beach girl whose lust for life takes her to Wollongong, Sydney, London, the Greek islands … and back to Sydney.

Protracted gestation

If Clift had completed The End of the Morning, it would not have been the first time readers had encountered Cressida Morley. She was a character who emerged, after a protracted gestation, through the novels of Clift’s husband, George Johnston.

Cressida was arguably first glimpsed as Charmian Anthony in the opening pages of Johnston’s Death Takes Small Bites (1948). The novel’s journalist-hero Cavendish C. Cavendish encounters Charmian adrift on the Burma Road. He is immediately taken by her lips “as pink as Danish salmon”, her eyes with the “same tint as glacier ice”, and a figure that is “slim and tight and stiff like a bullrush”.

When Cavendish asks what “a girl like you” is doing in remote China, Charmian responds: “Do I look like a missionary?” Cavendish realises he is “a little out of his depth”.

Johnston subsequently enlisted Clift as co-author on novels that drew on his wartime experiences in Asia, while inching forward with a series of sole-authored, increasingly autobiographical novels that invariably featured a Charmian doppelganger at the hero’s side.

In Closer to the Sun (1960), he presented for the first time David Meredith, his own alter-ego, with whom he is now forever associated. Meredith and his wife Kate battle to keep their fragile Greek island expatriation afloat.

Several years later, Johnston completed My Brother Jack (1964) – the first novel of his renowned “Meredith trilogy”. He called on Clift’s help, interrupting her attempts to use Cressida Morley to breathe life into her own roman à clef. When the dust settled on the wildly successful My Brother Jack, Meredith’s wife-to-be had transformed into Cressida Morley.

Stripped of her essence

At this point the famously close, complex and fractious relationship between Clift and Johnston became even more troubled. The depth of Clift’s creative crisis is artfully canvased by her biographer and editor Nadia Wheatley in an Afterword to The End of the Morning.