What we know about last year’s top 10 wild Australian climatic events – from fire and flood combos to cyclone-driven extreme rain

- Written by Laure Poncet, Research officer, UNSW Sydney

Fire. Flood. Fire and flood together. Double-whammy storms. Unprecedented rainfall. Heatwaves. Climate change is making some of Australia’s weather more extreme. In 2023, the country was hit by a broad range of particularly intense events, with economy-wide impacts. Winter was the warmest in a record going back to 1910, while we had the driest September since at least 1900.

We often see extreme weather as distinct events in the news. But it can be useful to look at what’s happening over the year.

Today, more than 30 of Australia’s leading climate scientists released a report analysing ten major weather events in 2023, from early fires to low snowpack to compound events.

Can we say how much climate change contributed to these events? Not yet. It normally takes several years of research before we can clearly say what role climate change played. But the longer term trends are well established – more frequent, more intense heatwaves over most of Australia, marine heatwave days more than doubling over the last century, and short, intense rainfall events intensifying in some areas.

What happened in 2023?

January. Event #1: Record-breaking rain in the north (NT, WA, QLD)

The year began with above-average rainfall in northern Australia influenced by the “triple-dip” La Niña phase.

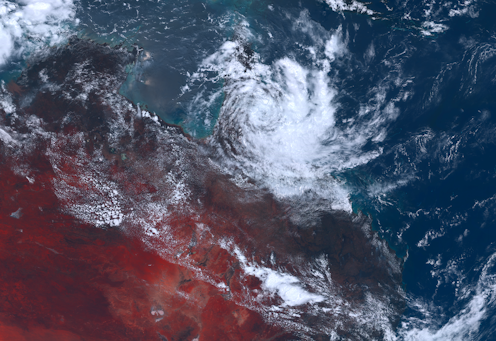

Some parts of the country were already experiencing heavy rainfall even before Cyclone Ellie arrived. From late December 2022 to early January 2023, Ellie brought heavy rainfall to Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, resulting in a one-in-100-year flooding of the Fitzroy River. Interestingly, Cyclone Ellie was only a “weak” Category 1 tropical cyclone. So why did it cause so much damage? In their analysis, climate scientists suggest it was actually low wind speeds in the mid-troposphere which allowed the system to stall and keep raining.

February–March. Event 2: Extreme rain and food shortages (NT, QLD)

Climate scientists observed the same behaviour from late February to early March 2023, when a persistent slow-moving low-pressure system known as a monsoonal low dumped heavy, widespread rain over the Northern Territory and north-west Queensland. The resulting floods cut transport routes in the NT, and led to food shortages.

June–August. Event 3 and 4: Warmest winter, little snow (NSW)

After a wet start to the year, conditions became drier and warmer in southern and eastern Australia. New South Wales experienced its warmest winter on record, with daily maximums more than 2°C above the long-term average.

The unusual heat and lack of precipitation translated into the second-worst snow season on record (the worst was 2006).

September. Event 5: Record heatwave (SA)

In September, South Australia faced a record-breaking heatwave. Temperatures reached as high as 38°C in Ceduna. As warming continues, scientists suggest unusual heat and heatwaves during the cool season will become more frequent and intense.

September also saw El Niño and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole declared by the Bureau of Meteorology. When these two climate drivers combine, we have a higher chance of a warm and dry Australia, particularly during late winter and spring.

October. Event 6, 7 and 8: Fire-and-flood compound event (VIC), compound wind and rain storms (TAS), unusually early fires (QLD)

Dry conditions gave rise to an unseasonably early fire season in Victoria and Queensland. In October, Queensland’s Western Downs region was hit hard. Dozens of houses and two lives were lost in the town of Tara.

The same month, Victoria’s Gippsland region was hit by back-to-back fires and floods, a phenomenon known as a compound event.

While it’s difficult to attribute these events to climate change, scientists say hot and dry winters make Australia more prone to early season fires.

Also in October, a different compound event struck Tasmania in the form of successive low-pressure systems. The first dumped a month’s worth of rain in a few days over much of the state, while the second brought strong winds. The rain from the first storm loosened the soil, making it easier for trees to be blown down.

Scientists say the combined effects were more severe than if just one of these events occurred without the other. Such extreme wind-and-rain compound events are expected to occur more frequently in regions such as the tropics as the climate continues to change.

November. Event 9: Supercell thunderstorm trashed crops (QLD)

In November, a supercell thunderstorm hit Queensland’s south-east, destroying A$50 million worth of crops and farming equipment. Initial research suggests extreme winds and thunderstorms may become more likely under climate change, but more work is needed.

December. Event 10: Unprecedented flooding from Cyclone Jasper (QLD)

In mid-December, Tropical Cyclone Jasper made landfall as a Category 2 tropical cyclone in north Queensland. The system weakened into a tropical low and then stalled over Cape York. The weather system’s northerly winds drew in moist air from the Coral Sea, which collided with drier winds from the south-east. This caused persistent heavy rainfall over the region – up to 2 metres in places. Catchments flooded across the region, causing widespread damage to roads, buildings and crops. Similar to ex-Tropical Cyclone Ellie, most damage occurred after landfall as the system stalled and dumped rain.

Climate change can make extreme weather even more extreme

It’s generally easier to identify and understand the role of human-caused climate change in large-scale extreme events, particularly temperature extremes. So we can say 2023’s exceptional winter heat was probably intensified by what we have done to the climate system.

For smaller-scale extremes, it is often harder to determine the role of climate change, but there’s some evidence short, intense rainfall events are getting even more intense as the world warms. Early-season bushfires and low snow cover are consistent with what we expect under global warming.

There’s also an increasing threat from the risk of compound events where concurrent or consecutive extreme events can amplify damage.

Australia’s intense weather events during 2023 are broadly what we can expect to see as the world keeps getting hotter and hotter due to the heat-trapping greenhouse gases humanity continues to emit.

Read more: Global heating may breach 1.5°C in 2024 – here's what that could look like

Authors: Laure Poncet, Research officer, UNSW Sydney