Drop the talk about 'mum and dad' landlords. It lets property investors off the hook

- Written by Peter Mares, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, School of Media, Film and Journalism, Monash University

Hardly a day passes without talk of “mum and dad” property investors. It’s media shorthand for a rental market dominated by small operators rather than big institutions.

But language shapes the way we think, and folksy terminology creates a false impression of Australia’s landlord class.

First, “mums and dads” conveys a 1950s, white-picket-fence version of Australia. Are no same-sex couples, singles or people without children investing in property? Plenty of parents with children rent, but we never hear them called “mum and dad tenants”.

Second, it gives the impression most landlords are average wage earners, struggling to build a modest nest egg and squeezed by high interest rates.

Yet, as I’ll explain, a majority of rental properties are owned by investors with multiple properties. And well-off investors enjoy the lion’s share of the tax benefits of policies like negative gearing.

Landlords are typically better off

The “mums and dads” rhetoric masks the reality of property ownership in Australia. Cue federal Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, defending negative gearing to support “mums and dads who save and, as part of their retirement income, put some money aside and buy a rental property”.

Or Victorian Property Council boss Cath Evans, rejecting rent control because “mum and dad investors” are struggling to get by on the income they get from tenants.

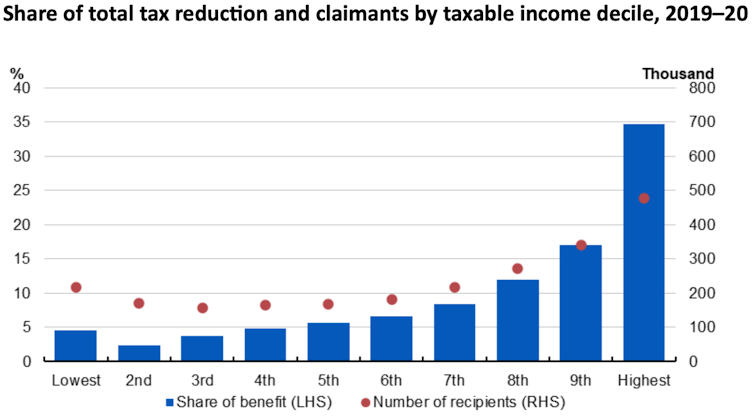

Treasury data show tax deductions for rental properties disproportionately benefit the well-off. More than a third of benefits go to about 500,000 landlords in the top 10% of income earners. About another third goes to the 20% immediately below them.

True, there are also about 200,000 landlords in the bottom 10% of income earners, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re poor. Treasury says this group “tend to have higher incomes”, but make “relatively large average deductions” that “substantially reduce their taxable income”.

Or as the Grattan Institute’s Danielle Wood puts it, “people who negatively gear have lower taxable incomes because they are negatively gearing”. (They may also be income-poor but asset-rich.)

High wage earners can borrow more to invest in property and have the most to gain from reducing tax through negative gearing. It’s no surprise cardiologists and politicians are more likely than school teachers and police officers to be landlords. The average federal MP owns at least two properties.

Who owns most rental properties?

Quality media outlets are not immune from the “mum and dad” language. This year it has cropped up in a Guardian explainer, an Age backgrounder and in at least two Conversation articles.

The ABC recently released What broke the rental market? by data journalist Casey Briggs. It’s a thorough and engaging examination of complex issues, but it recycles the “mum and dad” language and states that “the majority of rental properties in Australia are owned by landlords with just one investment property”.

This is wrong. A calculation based on the ATO’s individuals tax statistics shows why.

In 2021-22, about 1.6 million individuals, or about 70% of all landlords, declared a rental interest in a single property. So it’s true most investors own just one property.

But the other 30% — about 650,000 landlords — declared an interest in two or more properties. Almost 20,000 declared an interest in at least six.

If you multiply the number of landlords declaring multiple interests by the number of properties they declare, this suggests investors with multiple properties own just over half of all rental dwellings.

This is not new information. In its 2017 Financial Stability Review, the Reserve Bank noted “around half of investment properties are owned by investors with multiple properties”.

It is hard to be exact about numbers because many investors co-own properties, but these rough calculations are more likely to understate than overstate the extent of multiple property ownership. As research for the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute AHURI has noted, individual tax statistics exclude rental properties owned by businesses or held in other legal structures such as family trusts, residential property trusts or self-managed superannuation funds.

It’s common to conflate “most investors own only one rental property” with “most rental properties are owned by landlords with just one investment” and pointing out the error might seem pedantic. But it’s important to know that tenants are at least as likely to be renting from an investor with multiple properties as from a landlord with only one.

Landlords must be held to account

These facts challenge the “mum and dad” mythology that positions landlords as beneficent family members who do people a favour by allowing them to rent their homes.

Not every property investor is rich, and some landlords are on moderate incomes. And plenty of decent landlords do right by their tenants. But there are plenty of crap landlords too, letting out properties that are mouldy, or damp, or impossible to heat or cool, with windows you can’t open or doors you can’t lock.

Letting a house is not a cottage industry. The private rental market is a multibillion-dollar business. Investors get generous taxpayer subsidies and draw on professional real estate services to manage tenancies.

Yes, the numbers of small-scale operators cause problems in the rental market. There are solid arguments for encouraging institutional investment in build-to-rent projects.

But we should avoid language that portrays landlords as folk of modest means when most are well-off. It diverts attention from debates about reforming negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

Landlords engage in a business activity with profound impacts on the lives of others. They should be diligent in meeting their responsibilities.

Calling them “mums and dads” lets them off the hook.

Authors: Peter Mares, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, School of Media, Film and Journalism, Monash University