how Julie Andrews the child star embodied the hopes of post-war Britain

- Written by Brett Farmer, Lecturer in Film, Media and Communication, Deakin University

In June, the American Film Institute presented its 48th Life Achievement Award, the highest honour in American cinema, to the beloved stage-and-screen star Julie Andrews.

On conferring the award, the AFI praised Andrews as “a legendary actress” who “has enchanted and delighted audiences around the world with her uplifting and inspiring body of work”.

As anyone who has seen Mary Poppins (1964) or The Sound of Music (1965) can attest, “uplift” is central to the Julie Andrews screen persona.

It is a sweetness-and-light image that is easy to lampoon. Andrews herself is alleged to have quipped “sometimes I’m so sweet even I can’t stand it”. But it’s an element of feel-good edification that fuels much of the star’s iconic appeal.

The idea of Julie Andrews as a figure of uplift has a long history.

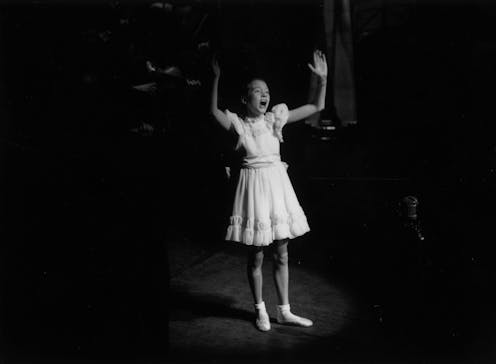

Decades before she attained global film stardom in Hollywood, Andrews enjoyed an early career as a child performer.

Billed as “Britain’s youngest singing star”, she performed widely on the postwar concert and variety circuit with forays into radio, gramophone recording and even early television.

Possessing a precociously mature soprano voice, Andrews was widely promoted in the era as a child prodigy. A 1945 BBC talent report filed when the young singer was just nine years old enthused over “this wonderful child discovery” whose “breath control, diction, and range is quite extraordinary for so young a child”.

Read more: How Austrians learned to stop worrying and love The Sound of Music

‘Infant prodigy of trills’

Andrews made her professional West End debut in 1947 where she dazzled audiences with a coloratura performance of the Polonaise from Mignon. Newspapers were ablaze with stories about the “12-year-old singing prodigy with the phenomenal voice”.

Reports claimed the pint-sized singer had a vocal range of over four octaves, a fully formed adult larynx and an upper whistle register so high dogs would be beckoned whenever she sang.

On the back of such stories, Andrews was given a slew of lionising monikers: “prima donna in pigtails”, “infant prodigy of trills”, “the miracle voice” and “Britain’s juvenile coloratura”.

While much of it was PR hype, the representation of Andrews as an extraordinary musical prodigy resonated deeply with postwar British audiences. The devastation of the war cast a long shadow, and there was a keen sense a collective social rejuvenation was needed to reestablish national wellbeing.

The figure of the child was pivotal to the rhetoric of postwar British reconstruction. From political calls for expanded child welfare to the era’s booming family-oriented consumerism, images of children saturated the cultural landscape, serving as a lightning rod for both social anxieties and hopes.

In her status as “Britain’s youngest singing star”, Andrews chimed with these postwar discourses of child-oriented renewal.

A popular myth even traced her prodigious talent to the very heart of the Blitz. Like a scene from a morale-boosting melodrama, the story claimed the young Andrews was huddled one night with family and friends in a Beckenham air raid shelter. In the middle of a communal singalong, a powerful voice suddenly materialised out of her tiny frame, astonishing all into silent delight.

Read more: Child stars: The power and the price of cuteness

‘Our Julie’

One of the most pointed alignments of Andrews’ juvenile stardom with a discourse of postwar British nationalism came with her appearance at the 1948 Royal Command Variety Performance.

Appearing just two weeks after her 13th birthday, Andrews was the youngest artist ever to participate in the annual event. It generated considerable media coverage and yet another grand nickname: “command singer in pigtails”.

Andrews performed a solo set at the event, and was also charged with leading the national anthem at the close.

Ideals of restorative nationalism shaped Andrews’ child stardom in other ways.

Much of her early repertoire was markedly British, drawn from the English classical canon and rounded out by traditional folk songs.

Press reports emphasised, for all her remarkable talent, “our Julie” was still a typical English girl thoroughly unspoiled by fame. In accompanying images she would appear in idyllic scenarios of classic English childhood: playing with dolls, riding her bicycle, doing her homework.

Elsewhere, commentary was rife with speculations about Andrews’ prospects as “the next Adelina Patti” or “future Lily Pons”. The mix of nostalgia and hope helped make the young Andrews a reassuring figure in the anxious landscape of postwar Britain.

All grown up

Little prodigies can’t remain little forever. There lies the troubled rub for many child stars, doomed by biology to lose their principal claim to fame.

In Andrews’ case, she was able to make the successful transition to adult stardom – and even greater fame – by moving country and professional register into the American stage and screen musical.

Still, the themes of therapeutic uplift that defined her early child stardom would follow Julie Andrews as she graduated to become the world’s favourite singing nanny.

Authors: Brett Farmer, Lecturer in Film, Media and Communication, Deakin University