the Australian story of Mikis Theodorakis' legendary song Zorba

- Written by Andonis Piperoglou, Adjunct Research Fellow, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University

For those with only a cursory familiarity with Greece and Greek music, the name of Mikis Theodorakis, who died last week aged 96, may conjure flashbacks to the 1964 film Zorba the Greek . That moment on a Cretan beach when Alexis (Anthony Quinn) teaches Basil (Alan Bates) how to dance the sirtaki, now universally known as the “Zorba dance”, is etched into our collective memory.

Born in 1925, Theodorakis began writing music when he was a child. During his lifetime, he was a political figure as much as a composer. Under the Greek junta (1967-1974) the dictatorship banned his music. Theodorakis was jailed, tortured, put under house arrest and, from 1970 until 1974, lived in exile. His Journals of Resistance (1973) was a statement of defiance to the military regime.

As a composer he fused poetry and popular musical idioms, achieving wide appeal at home and abroad. Reworking Greek folk rhythms, he incorporated past tradition with present inspiration and future hope. His Mauthausen Trilogy, a cycle of four arias composed in 1965, is credited as a standout composition on the Holocaust.

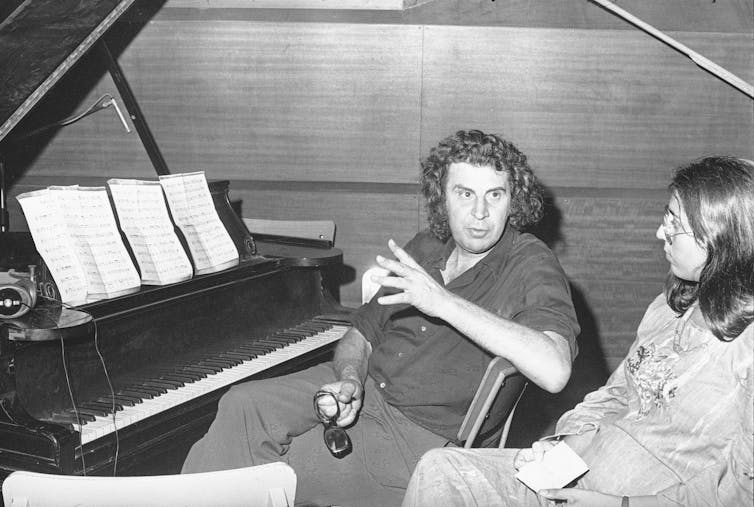

Theodorakis talks to Greek singer Maria Farandouri during a break at an Athens recording studio, 1974.

AP Photo/Aristotle Saris, File

Theodorakis talks to Greek singer Maria Farandouri during a break at an Athens recording studio, 1974.

AP Photo/Aristotle Saris, File

His composition of the Zorba is one of the most recognisable sounds of the 20th century. Its accompanying dance — with its slow, smooth actions that gradually transform into faster, more vivid movements in unison with the metallic sound of the bouzouki — is both loved and despised.

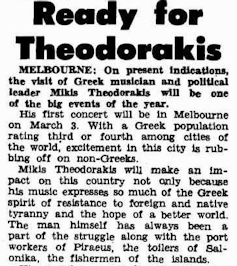

An article about Theodorakis’ tour, as it appeared in the Tribune, 22 February 1972.

Trove

An article about Theodorakis’ tour, as it appeared in the Tribune, 22 February 1972.

Trove

His 1972 Australian tour

In 1972, while still living in exile, Theodorakis toured Australia. The Tribune newspaper called it “one of the big events of the year” which would be enjoyed by both “Greek migrants and other Australians”.

Interviewed in Melbourne, also for the Tribune, one Greek migrant expressed her elation: “Do you see what Theodorakis means to our country? […] The best poetry in the country was being sung in the streets to his music.”

Coinciding with an emergent Australian multicultural ethos, Theodorakis’ concerts also prompted a critique of the country’s desire to assimilate migrants.

If Greek culture is lost to us by assimilation […] rather than retained and developed by its integration into a multi-nation, multi-racial Australia, a crime will have been committed.

The Communist Party of Australia also praised his tour. In a statement, Greek members of the party said:

Never before in the history of Greeks in Australia has there been such an immense and spontaneous popular excitation for the Greece of struggle, justice and beauty as has happened during the Theodorakis concerts.

Theodorakis clearly ignited impassioned sentiments.

A few years after his tour, the White Australia Policy would be abolished, and multiculturalism would become official state doctrine, with Zorba becoming a mainstay at multicultural festivals.

Read more: Australian politics explainer: the White Australia policy

An Australian multicultural dance

Promoting cultural retention, these performances have contributed to the formation of a Greek Australian identity.

Greek festivals bring Australians from differing regional backgrounds together, and the dance has contributed to how Greekness can be acquired and expressed. For third or fourth generation children of Greek background — who often lack Greek language skills — learning Zorba facilitates an awareness of distinctive ethnic roots.

Read more: ‘Where are you from?’ is a complicated question. This is how young Australians answer

The performance isn’t limited to the Greek community. It has spread to be taught in school sports classes and performed at events like the Sydney Olympics and at the NRL’s multicultural round.

In 2018, as part of the Melborune’s Lonsdale Street Greek Festival, attempts were made via a “Big Fat Greek Flashmob” to set a world record for the largest number of people dancing to the familiar tune. They were unable to beat the record of 5,614 people in Volos, Greece, in 2012.

But perhaps the most famous rendition of the dance came from an unexpected source.

Remastering Zorba, Yolngu Style

In 2007 a group of young Yolngu dancers from Elcho Island made global headlines. The Chooky Dancers (later renamed Djuki Mala) became famous when Frank Djirrimbilpilwuy uploaded an inconspicuous video recording on YouTube.

The viewer awaits a traditional dance routine. Instead, the young men move in sync to a pop techno remix of Zorba, performing movements usually reserved for Greek weddings and christenings.

As a way of saying thank you to a Greek friend named Liliane, the dance strengthened the relationship between Yolngu people and the Northern Territory’s Greek community.

The video went viral. Djuki Mala performed their hit on Australia’s Got Talent and toured Europe and the Middle East, including an invitation from Theodorakis’s family to dance in Athens.

The original video has now been viewed over three million times. It remains an uplifting cultural accomplishment: both poking fun at and remastering Zorba.

A way of sharing of Yonglu cultural expression, and a hallmark example of the way Greek Australian culture has become firmly part of the fabric of modern Australia.

Read more: What's so funny about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander humour?

Authors: Andonis Piperoglou, Adjunct Research Fellow, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University