the Snake Creek Tracksite unveiled

- Written by Stephen Poropat, Adjunct Researcher, Swinburne University of Technology

Fossilised bones belonging to enormous long-necked sauropod dinosaurs have been known from western Queensland since the 1930s, when Austrosaurus mckillopi was discovered on Clutha Station near Maxwelton. Since then, western Queensland has yielded many more sauropod bones and skeletons, particularly in the past two decades.

But the footprints of these behemoths, which can reveal much about how they behaved in life, remained elusive until 2016 when we and our colleagues at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum were informed about sauropod tracks dating back some 95 million years at Karoola Station, northwest of Winton.

Harry Elliott, Bob Elliott, and Stephen Poropat at the Snake Creek Tracksite on June 10th, 2016.

Trish Sloan/AAOD

Harry Elliott, Bob Elliott, and Stephen Poropat at the Snake Creek Tracksite on June 10th, 2016.

Trish Sloan/AAOD

The tracksite, which we named “Snake Creek”, comprises a layer of siltstone less than a metre thick, as wide as a basketball court and twice as long. Ninety-five million years ago, this was a silt flat situated between a billabong and a meandering river. We describe the footprints preserved at the Snake Creek Tracksite in a new paper, published in PeerJ.

Over the course of more than two years, the tracksite was excavated and moved in its entirety to a purpose-built facility at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs (AAOD) Museum in Winton, where it is now open to the public.

A snapshot of a prehistoric menagerie

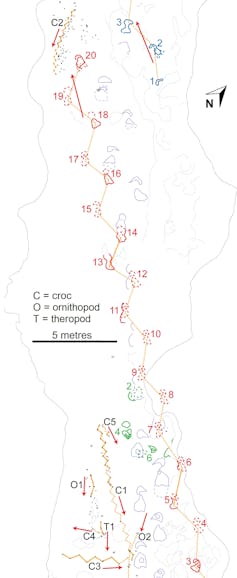

Close up of the Snake Creek Tracksite showing the direction of the various animals. Several crocs and all of the small theropod and ornithopod dinosaurs moved from northeast to southwest (and, therefore, in the opposite direction to the sauropods). Other crocs crossed the tracksite perpendicular to the rest.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Close up of the Snake Creek Tracksite showing the direction of the various animals. Several crocs and all of the small theropod and ornithopod dinosaurs moved from northeast to southwest (and, therefore, in the opposite direction to the sauropods). Other crocs crossed the tracksite perpendicular to the rest.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

The largest footprints at the Snake Creek Tracksite were made by sauropod dinosaurs. Sauropods walked on all fours, and the front and back feet left very different prints.

The front footprints are crescent-shaped, whereas the back feet are oval with a front taper. At least four individual sauropods walked across the tracksite in the same direction within a very narrow time frame.

The sauropod footprints appear to have been made when the tracksite was not underwater. They are surrounded by concentric ridges that imply brittle deformation of the silt, and many have blobs of siltstone in the middle (called “adhesion traces”) that show where sediment pooled after the animal lifted its foot.

One of the sauropod footprints had a surprise in store: a single three-toed footprint preserved within. This appears to have been made by a medium-sized, meat-eating theropod dinosaur, similar to Winton’s own Australovenator wintonensis, that crossed the tracksite before the sauropod when the silt was still fairly wet at depth.

Read more: Introducing Australotitan: Australia's largest dinosaur yet spanned the length of 2 buses

Sauropod footprints at the Snake Creek Tracksite. The front footprint (towards the top of the page) is crescent-shaped, whereas the back footprint is oval but tapered to the front and indented behind. The blob in the middle of the back footprint is a solidified mass of silt. Ridges encircle the footprints, which are also surrounded by footprints from smaller animals.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Sauropod footprints at the Snake Creek Tracksite. The front footprint (towards the top of the page) is crescent-shaped, whereas the back footprint is oval but tapered to the front and indented behind. The blob in the middle of the back footprint is a solidified mass of silt. Ridges encircle the footprints, which are also surrounded by footprints from smaller animals.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Most of the other footprints at the tracksite appear to have been made after the sauropod footprints, by animals buoyed up in water. Parallel to the sauropod tracks but running in the opposite direction are several trackways of small, three-toed footprints.

Initially, we thought all of these footprints were from small-bodied theropod and ornithopod dinosaurs, similar to those at the nearby Lark Quarry Conservation Park. However, closer examination of the relative lengths of the toes and the width of the trackways revealed that some were not — at least four of the trackways were made by ancient relatives of modern crocodiles called crocodyliforms.

The absence of belly or tail drag marks, coupled with the scarcity of front footprints, means it is likely the crocodyliforms were swimming in shallow water, pushing off the bottom periodically with their back feet to propel themselves along.

Read more: Prehistoric 'river boss' is the largest extinct croc species ever discovered in Australia

A three-toed crocodyliform footprint (right) overprinting a three-toed small theropod dinosaur footprint (left).

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

A three-toed crocodyliform footprint (right) overprinting a three-toed small theropod dinosaur footprint (left).

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Other footprints at the Tracksite appear to be those of swimming turtles that touched down very rarely. Perhaps the most unusual traces are not footprints at all: they are horseshoe-shaped divots that appear to have been left by bottom-feeding lungfish.

Possible lungfish feeding trace.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Possible lungfish feeding trace.

Stephen Poropat/AAOD

Protecting the Tracksite

Fossilised footprints require conservation if they are to be protected from weathering and erosion. They are often moulded with latex and cast in plaster or resin to create replicas for further study.

Much more rarely, fossilised footprints or trackways may be removed wholesale to a museum. The most notable example before now was the relocation of a relatively small section of a tracksite from the Paluxy River in Texas to the American Museum of Natural History in New York in the 1940s.

In 2018, the Australian Age of Dinosaurs (AAOD) Museum set out to relocate and preserve the entire Snake Creek Tracksite, which was at risk of erosion from periodic flooding in Snake Creek.

Between April 2018 and November 2020 a small team of AAOD Museum staff and volunteers systematically removed hundreds of tonnes of rock from Karoola Station to the AAOD Museum.

Anna Tzamouzaki, Christine Heller, and Judy Elliott formed the core of the team that relocated the Snake Creek Tracksite. Each of these women spent more than a year on site, painstakingly removing sections of Tracksite piece by piece, loading them for transport, then reassembling them at the AAOD Museum.

AAOD

Anna Tzamouzaki, Christine Heller, and Judy Elliott formed the core of the team that relocated the Snake Creek Tracksite. Each of these women spent more than a year on site, painstakingly removing sections of Tracksite piece by piece, loading them for transport, then reassembling them at the AAOD Museum.

AAOD

In May 2021, the new home of the Snake Creek Tracksite was opened to the public: a temperature-controlled, 885-square-metre building at the AAOD Museum in Winton, set up with the help of funding from the Queensland Government. The tracksite will now be accessible to future researchers, and offers a glimpse of a long-lost ecosystem in Australia’s deep past to any visitors to town.

An inside view of the March of the Titanosaurs exhibition at the AAOD Museum.

Steven Lippis/AAOD

An inside view of the March of the Titanosaurs exhibition at the AAOD Museum.

Steven Lippis/AAOD

Read more: A new look at a lost dinosaur dig in the Australian outback

Authors: Stephen Poropat, Adjunct Researcher, Swinburne University of Technology

Read more https://theconversation.com/the-march-of-the-titanosaurs-the-snake-creek-tracksite-unveiled-161039