Pompeii is famous for its ruins and bodies, but what about its wine?

- Written by Emlyn Dodd, Greece Fellow, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens; Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Centre for Ancient Cultural Heritage and Environment, Macquarie University

Pompeii is famed for plaster-cast bodies, ruins, frescoes and the rare snapshot it provides of a rather typical ancient Roman city. But less famous is its evidence of viticulture.

Wild grapevines probably existed across peninsular Italy since prehistory, but it is likely the Etruscans and colonising Greeks promoted wine-making with domesticated grapes as early as 1000 BCE.

Pompeii, preserved after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, sits within Campania on fertile volcanic soil with a temperate Mediterranean climate and reliable sources of water.

Pliny the Elder, living nearby Pompeii in 77 CE wrote of the “vine-growing hills and noble wine of Campania” and the poet Martial described vats dripping with grapes, and the “ridges Bacchus loved more than the hills of Nysa”.

The Greeks even referred to Campania as Oenotria – “the land of vines”.

A fresco found in Pompeii, painted c 55-79 CE, depicting Bacchus covered in grapes and Vesuvius with trellised vines in background.

Naples Archaeological Museum

A fresco found in Pompeii, painted c 55-79 CE, depicting Bacchus covered in grapes and Vesuvius with trellised vines in background.

Naples Archaeological Museum

A famous wine region

Over 150 Roman farms have been discovered in the Vesuvian region, and many engaged in viticulture. Some of the most famous ancient wines came from this region, including the honey-sweet and expensive Falernian wine.

Falernian was said to ignite when a flame was applied, suggesting an alcohol content of at least 40% – significantly higher than the 11% you could expect to buy from the bottle shop today.

While the Falernian was believed to be white, most ancient wines were red due to the less laborious production process.

A wide variety of wines could be found on the Roman wine market, flavoured with sea water, resin, spices and herbs like lavender and thyme, or even fermented in a smoke-filled room to impart flavour.

Vineyards are still planted in Pompeii today.

Wikimedia Commons

Vineyards are still planted in Pompeii today.

Wikimedia Commons

There is even possible evidence for early counterfeit wine. Archaeologists have identified imitation ceramic transport jars produced elsewhere and stamped with fake Pompeian merchant stamps.

Agriculture among an ancient city

Within Pompeii’s city walls, vineyards hid behind taverns and inns as families and bar-keepers grew grapes on a smaller scale for their own tables and wine.

When vines were covered by the volcanic eruption and later decomposed, they left cavities in the debris. By filling these cavities with plaster, archaeologists were able to reveal vineyards over entire city blocks.

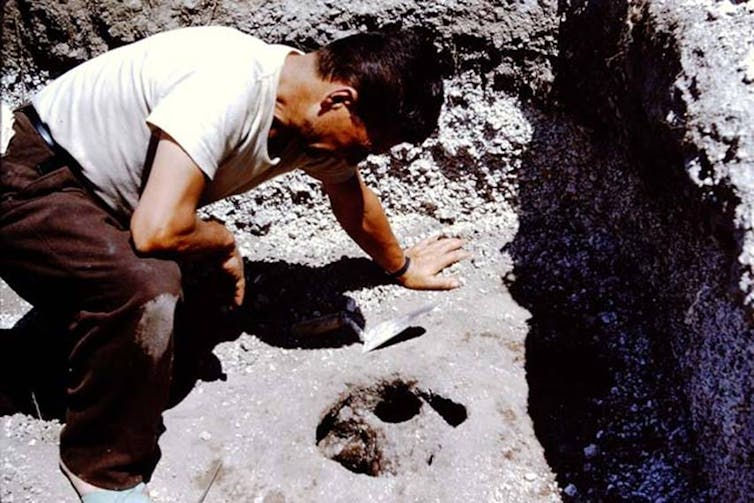

A large cavity formed by roots discovered in 1966.

The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections, CC BY-NC-SA

A large cavity formed by roots discovered in 1966.

The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections, CC BY-NC-SA

Excavations have revealed carbonised grape seeds and even whole preserved grapes caramelised from the volcanic eruption – their high sugar content gives them a glassy appearance easily spotted amongst the soil.

Gardens were everywhere in Pompeii. The archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski noticed at least one in each house and, in some larger elite residences, up to three or four. Many included vines to grow grapes for fruit and wine, but also to provide shade over triclinia dining areas.

If you visit the modern town surrounding Pompeii today, you will notice not much has changed in 2,000 years.

Read more: Walking, talking and showing off – a history of Roman gardens

The ‘Foro Boario’ vineyard

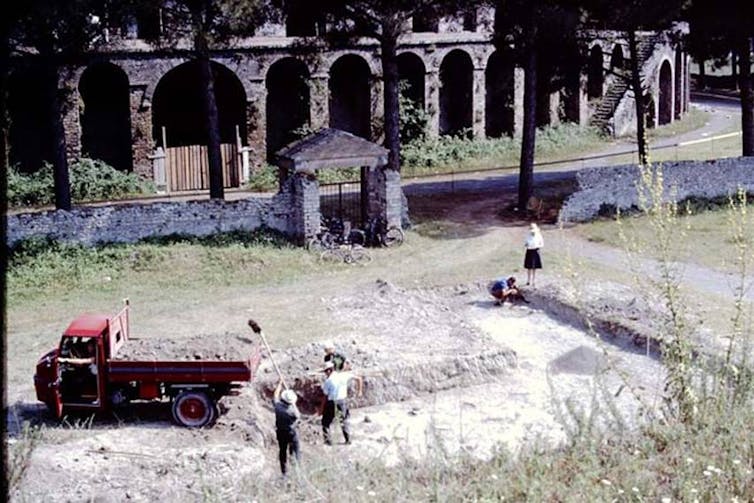

Opposite Pompeii’s amphitheatre is the Foro Boario. Misnamed because archaeologists originally thought the site was a cattle market, excavations in the 1960s revealed it was once actually an extensive vineyard.

Over 2,000 vines were found, with almost the exact spacing between each vine as recommended by the ancient agricultural writers Pliny and Columella. Each vine was attached to a stake and 58 fruit trees were also planted in the vineyard.

Local workers at the time of excavation even commented that the four depressions found around root cavities were identical to the holes holding water in their own vineyards.

Excavations in 1966 revealed the area in front of the amphitheatre was once a vineyard.

The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections, CC BY-NC-SA

Excavations in 1966 revealed the area in front of the amphitheatre was once a vineyard.

The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections, CC BY-NC-SA

At the back of the vineyard was found a small two-room structure housing a lever wine press and ten dolia – large ceramic fermentation jars buried into the ground to keep temperatures consistently cool.

There are also numerous triclinia for eating and drinking scattered among the vineyard, suggesting the owner did a thriving business opposite the amphitheatre, with gladiatorial patrons coming to relax, eat and drink before and after spectacles.

Resurrecting ancient wine

That such large and valuable pieces of land within the city walls were dedicated to wine-making gives insight to the profitable nature and high esteem viticulture held in Roman communities.

A Roman Feast depicted by Roberto Bompiani in the late 19th century.

Getty Museum

A Roman Feast depicted by Roberto Bompiani in the late 19th century.

Getty Museum

Today, many of these vineyards have been replanted as they were at the time of the eruption, with relatives of ancient grape varieties like the Piedirosso: a fruity and floral grape with light herb and spiced flavours, perhaps related to Pliny’s ancient Columbina variety.

Read more: Wine and climate change: 8,000 years of adaptation

In 1996, the local Campanian winemaker, Mastroberardino, cultivated and processed these grapes using Roman techniques and created the Villa dei Misteri wine: ruby red in colour with a complex taste, including hints of vanilla, cinnamon and notes of spice and cherry.

It can be aged for 30 years or more – just like the 60-year-old Falernian drunk by Julius Caesar at his celebration banquet in 60 BC.

Authors: Emlyn Dodd, Greece Fellow, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens; Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Centre for Ancient Cultural Heritage and Environment, Macquarie University