the Mars rover searching for ancient life, and the Aussie scientists who helped build it

- Written by David Flannery, Planetary Scientist, Queensland University of Technology

Every two years or so, when Mars passes close to Earth in its orbit around the Sun, conditions are right to launch a spacecraft to the red planet. Launches during this period can complete the seven-month voyage using a minimum of energy.

We are in the middle of one such period right now, and three separate missions are taking advantage of it. The United Arab Emirates’ Hope mission and China’s Tianwen-1 have already launched. NASA’s Perseverance mission is set to take flight tonight (on July 30, at 9:50pm AEST).

Between them, the missions will study the atmosphere and surface of Mars in unprecedented detail, collect samples that may one day come back to Earth, and tell scientists more about whether our neighbouring planet ever held life.

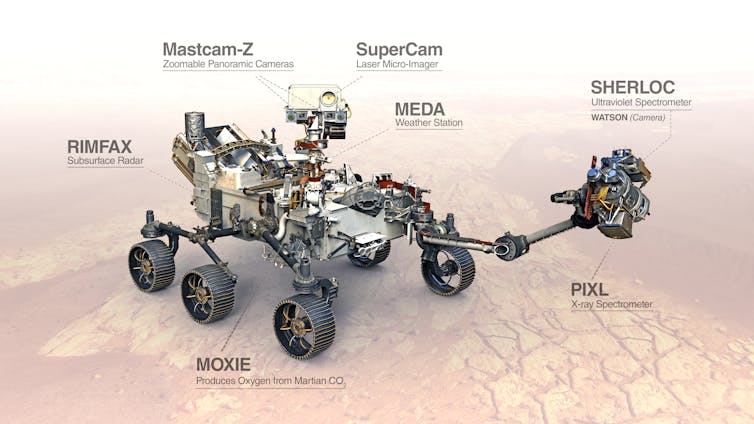

Instruments carried aboard NASA’s Perseverance Rover.

NASA JPL/Caltech

Instruments carried aboard NASA’s Perseverance Rover.

NASA JPL/Caltech

Read more: Our long fascination with the journey to Mars

What do the Mars missions aim to achieve?

The UAE’s Hope orbiter will study the atmosphere of Mars using infrared and ultraviolet light.

In a truly international effort, Hope’s instruments were developed by scientists at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in Dubai, working with the University of Colorado, Boulder, and Arizona State University in the United States. Hope was carried from Dubai to Japan by a Russian-operated Antonov aircraft, and launched from Tanegashima Island on July 19.

Hope has no doubt already achieved its primary goal of inspiring the youth of the Arab world. Like most deep space missions, Hope’s goals are a combination of cutting-edge science, technology demonstration, and stimulating the local knowledge economy.

Although accompanied by less fanfare, China’s Tianwen-1 mission is also an extraordinarily ambitious effort driven by clear scientific goals. Building on the success of China’s lunar exploration program, Tianwen is the country’s first attempt at a Mars rover. If Tianwen succeeds, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) will become the second space agency after NASA to operate a rover on Mars.

Tianwen-1 undergoing testing in China.

Tianwen-1 undergoing testing in China.

Both the rover and accompanying orbiter will bring instruments that address key questions of the global scientific community.

Tianwen will carry a ground-penetrating radar that will let geologists peer beneath the dusty surface to examine the rock beneath the landing site. It will also carry the first mobile instrument that can sense variations in the magnetic field, which may tell scientists a lot about how fit for life Mars was in the past.

Tianwen-1 launched on July 23 from Hainan Island. Unfortunately, mission scientists were forbidden from talking to media beforehand, and live videos of the launch were banned (though some snuck out online).

The launch of China’s Tianwen-1 Mars mission on the 23rd of July, 2020.

The launch of China’s Tianwen-1 Mars mission on the 23rd of July, 2020.

China has now demonstrated a super heavy launch system to deep space, and if it succeeds with a soft landing on Mars and deep space operations, it will be close on NASA’s heels in Mars sample return. The idea of a Chinese Mars mission getting the first answers to big questions in planetary science, which would have seemed unlikely only a few years ago, may well become reality in the coming months. Both the Chinese and American programs have plans to return Martian samples to Earth in the 2030s.

Perseverance and the search for ancient life

For now, NASA is still the player with the most experience and the best resources. The Perseverance rover, scheduled for launch from Florida on July 30 at 9:50pm AEST, will be the most complex object ever sent to Mars. The new rover will search for evidence of ancient microbial life in Jezero Crater.

Read more: Ancient life in Greenland and the search for life on Mars

Perseverance is the first in a series of missions that NASA hopes will culminate in bringing samples of the Martian surface back to Earth. A novel system will collect samples selected by a globally distributed team of experts and cache them for future collection. These rocks will likely be studied for decades, like the samples of Moon rock brought home by the Apollo missions.

Italy, Norway and Denmark are among the smaller nations contributing hardware to Perseverance. The scientists and engineers who participate gain experience with deep space systems, share in discoveries and increase the overall scientific gains of the project.

How Australians are involved

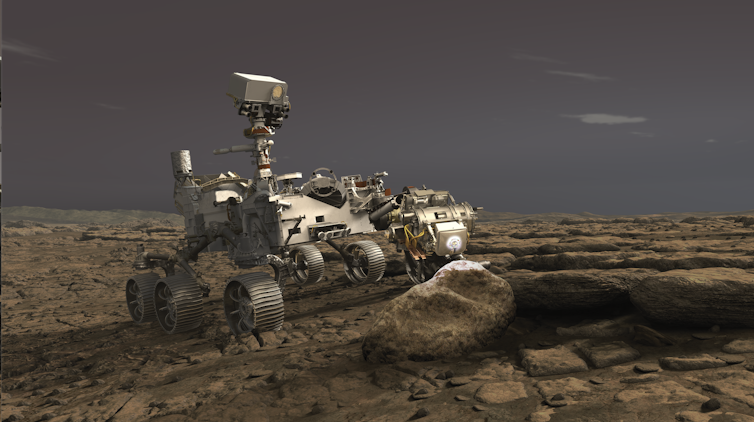

Artists impression of the Planetary Instrument of X-ray Lithochemistry aboard the Perserverance Rover, led by Australian scientists, analysing rocks on Mars.

Artists impression of the Planetary Instrument of X-ray Lithochemistry aboard the Perserverance Rover, led by Australian scientists, analysing rocks on Mars.

Microbial fossil stromatolite in Western Australia (left) sampled by prototype rover drill hardware in a collaboration with NASA JPL. The stable carbon isotope composition of microfossils captured in the drill core was measured using secondary ion mass spectrometry (right).

Microbial fossil stromatolite in Western Australia (left) sampled by prototype rover drill hardware in a collaboration with NASA JPL. The stable carbon isotope composition of microfossils captured in the drill core was measured using secondary ion mass spectrometry (right).

Several Australians are also involved in the Perseverance mission.

Brisbane-born geologist Abigail Allwood, based at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, leads the team who developed an instrument on the rover’s arm capable of detecting signs of past life. Australian planetary scientist Adrian Brown is also working on the mission, bringing his experience using remote sensing to study Australian rocks that resemble those on Mars.

I worked on this mission at NASA JPL for several years and, although I have returned to Australia, I continue to serve as a long-term planner leading the mission’s science team and as an instrument co-investigator. The Queensland University of Technology is contributing software that will analyse data returned from the rover, with opportunities for Australian students and academics to contribute to the science investigation.

The geology of Jezero Crater mapped by the Perseverance mission science team including Australians bringing expertise studying similar rocks in Western Australia.

NASA JPL/Caltech

The geology of Jezero Crater mapped by the Perseverance mission science team including Australians bringing expertise studying similar rocks in Western Australia.

NASA JPL/Caltech

The future

Australia is well placed to make important contributions to the future of Mars exploration. But to do so we must collaborate across national borders and find our place in the international scientific framework.

The planning of the nascent Australian Space Agency has largely focused on creating jobs and nurturing industry, but it needs a list of scientific priorities to guide investment in space missions. Otherwise, we risk building a car that is missing the driver’s seat.

At successful space agencies overseas, engineers and private industry work with scientists who conceive and operate spacecraft in pursuit of truth. Employment and innovation come from scientific projects, not the other way around. By following this model, Australia too may join the exploration of the universe, spurring technological innovation and inspiring the next generation of humans in the process.

Read more: Why isn't Australia in deep space?

Authors: David Flannery, Planetary Scientist, Queensland University of Technology