the self-surveillance strategy to keep supermarket shoppers honest

- Written by Gary Mortimer, Professor of Marketing and Consumer Behaviour, Queensland University of Technology

Retailers have tried many overt tactics to limit theft, such as signs that display images of CCTV cameras, threats to prosecute offenders, bag checks, checkout weighing plates and electronic security gates.

These tactics are extremely costly and have failed to stamp out retail theft.

Now supermarkets are trying a different tactic, that’s part overt surveillance but also encourages “self-reflection” on any impulse to exploit loopholes in the bagging and payment systems.

In late May Australian supermarket giant Woolworths confirmed it is trialling self-service checkout terminals with built-in cameras. They display your image as you scan your items. Rival Coles started trying the technology in April 2019.

The idea is that watching yourself scan your own groceries will reduce the temptation to steal. It is supported by research that shows the effectiveness of cues that cause us to self-focus and self-regulate.

Retail theft continues to grow

Since 1990, when the Australian Insitute of Criminology published extensive research on retail crime and its prevention, it has been widely accepted crime-related losses account for about 1% of all retail revenue. Estimates of customer theft were woolier.

In August 2019 the Australia and New Zealand Retail Crime Survey came up with a specific number. It reported total crime-related retail losses amounted to 0.92% of revenue. Customer crime was 58% of that – or 0.53% of total revenue.

Though funded by retail technology company Checkpoint Systems, the survey sample is robust – almost a quarter of the retail industry in Australia and New Zealand. Also, the lead researcher, Emmeline Taylor, is a criminologist in the Department of Sociology at City, University of London respected for her expertise in retail crime.

Costs of loss prevention

Writing about her research in 2018, Taylor tells the story of a major Australian supermarket discovering it was selling more carrots than it had in stock.

Unfortunately this wasn’t a sudden switch to healthy eating or a desire to increase vitamin C intake, it was an early sign of a new type of shoplifter. Otherwise honest shoppers were using the self-service checkout to transact more expensive items – typically avocados – and put them through as carrots.

Self-service checkouts have enabled ‘swipers’ – seemingly well-intentioned patrons engaging in routine shoplifting, says criminologist Emmeline Taylor.

Shutterstock

Self-service checkouts have enabled ‘swipers’ – seemingly well-intentioned patrons engaging in routine shoplifting, says criminologist Emmeline Taylor.

Shutterstock

She termed these self-service checkout thieves “SWIPERS” – seemingly well- intentioned patrons engaging in routine shoplifting. As the Australia and New Zealand Retail Crime Survey states:

Their behaviour and motivations (that are often interlinked) fall into four main groups: the accidental thieves, the switchers of labels, those compensating themselves, and those that steal because they claim to have become frustrated with the process of self-checkout (e.g. triggering alerts or purchasing age-restricted items that require assistance from an employee).

Read more: The economics of self-service checkouts

Prevention techniques

The traditional approach to loss prevention involves attendants and security guards, specialised display fixtures, reinforced packaging, training, in-store signage, display alarms and more cameras.

More of these can prove counter-productive, as highlighted by the Australian Institute of Criminology’s analysis of local crime prevention strategies in 2014. It found, for example, that introducing surveillance systems or security guards made shop staff less likely to approach suspicious shoppers.

Getting away with it

The research by Taylor and others into the motivators of shoplifting points to the potential of another way to reinforce honest behaviour.

While some forms of stealing might be considered irrational – such as kleptomania – shoplifters often rationalise their thefts.

Read more: How shoplifters justify theft at supermarket self-service checkouts

How much they steal comes down to their own “deviance threshold” – the point at which they can no longer justify their behaviour alongside a self-perception as a good person. This helps explains the greater frequency of shoplifting lower value items. It’s easier to justify a small “discount” on your bill.

If it’s just a small theft, also, the chances of getting caught are smaller. If caught, the chance of getting away – passing it off as an honest mistake, perhaps – is higher. This semi-conscious calculation is known as the “denial of punishment probability”.

You are being watched

An obvious strategy for retailers is to make shoppers more aware they are being watched.

Research has demonstrated “eyes” images do this more effectively than images of security cameras or written reminders such as “you are being observed”. This is due to eyes triggering instincts connected to our evolutionary capacity for gaze detection – sensitivity to being watched.

Read more: Super-recognisers accurately pick out a face in a crowd – but can this skill be taught?

But eyes signs also have their limitations.

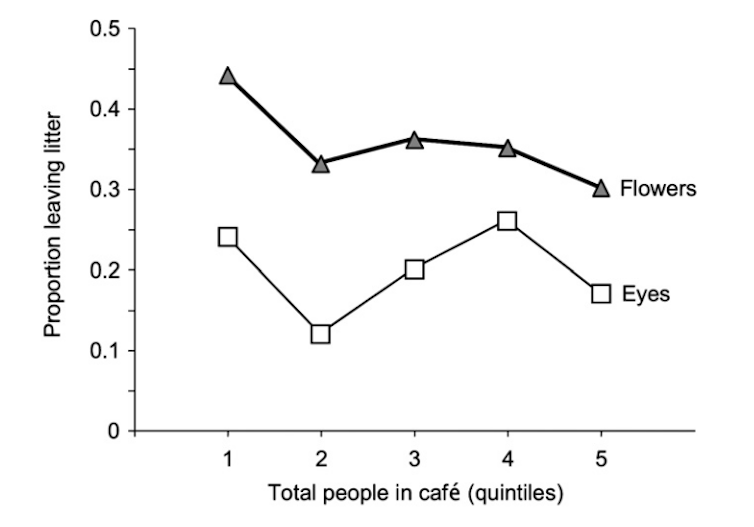

Newcastle University researchers Max Ernest-Jonesa, Daniel Nettleb and Melissa Bateson did an experiment in a campus cafeteria and found that posters featuring eye images resulted in less litter being left on tables than images of flowers, but less so when the café was busier.

Proportion of tables with litter left by quintile of number of people in the café at the time (1=fewest people, 5=most) under eye-image and flower-image conditions.

Max Ernest-Jones, Daniel Nettle, Melissa Bateson, CC BY-NC-ND

Proportion of tables with litter left by quintile of number of people in the café at the time (1=fewest people, 5=most) under eye-image and flower-image conditions.

Max Ernest-Jones, Daniel Nettle, Melissa Bateson, CC BY-NC-ND

The more people around the more we relax. Those “eyes” can’t be watching everyone.

Think of yourself

An more effective tactic might be appealing to another honed evolutionary instinct: a “think of yourself” focus.

University of East Anglia researcher Rose Melaeady and colleagues demonstrated this with experiments using signs to encourage drivers to turn off their engines at a busy rail crossing with a two-minute average wait.

After an experiment just using an “watching eyes” image (with no discernible effect) they tried two signs.

One with set of human eyes and the words: “When barriers are down, switch off your engine”

The other with just the words: “Think of yourself: When barriers are down, switch off your engine.”

Rose Meleady et al, Environment and Behavior, February 10 2017., CC BY-NC-ND

With no sign, 20% of drivers switched off their engines. With the watching eyes sign, 30% switched off. With the “think of yourself” sign, 51% did so.

Self-surveillance

So the supermarkets’ self-surveillance strategy combines two tactics. First, a “traditional” external motivation to do the right thing – amplifying the spotlight effect with an overt reminder we are being watched. Second, it is also intended to evoke self-reflection and self-regulation.

These steps will likely add to concerns about personal privacy, though Woolworths and Coles say no recordings are being made.

Read more:

From fare evasion to illegal downloads: the cost of defiance

Even if they were, though, the embrace of cashless transactions – with just 27% of all payments now made with cash – suggests most customers aren’t overtly concerned about how much others know about their shopping habits.

Rose Meleady et al, Environment and Behavior, February 10 2017., CC BY-NC-ND

With no sign, 20% of drivers switched off their engines. With the watching eyes sign, 30% switched off. With the “think of yourself” sign, 51% did so.

Self-surveillance

So the supermarkets’ self-surveillance strategy combines two tactics. First, a “traditional” external motivation to do the right thing – amplifying the spotlight effect with an overt reminder we are being watched. Second, it is also intended to evoke self-reflection and self-regulation.

These steps will likely add to concerns about personal privacy, though Woolworths and Coles say no recordings are being made.

Read more:

From fare evasion to illegal downloads: the cost of defiance

Even if they were, though, the embrace of cashless transactions – with just 27% of all payments now made with cash – suggests most customers aren’t overtly concerned about how much others know about their shopping habits.

Authors: Gary Mortimer, Professor of Marketing and Consumer Behaviour, Queensland University of Technology