Let's untangle the murky politics around kids and food (and ditch the guilt)

- Written by Jane Martin, Executive Manager of the Obesity Policy Coalition; Senior Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne

This article is part of a series focusing on the politics of food – what we eat, how our views of food are changing and why it matters from a cultural and political standpoint.

Naturally, parents want the best for their children. While they shouldn’t chastise themselves for offering the occasional treat, what used to be an “occasional” treat is becoming something that’s “every day”, or “several times a day”.

When around one-third of the average child’s energy intake comes from processed junk foods, it’s clearly hard to stick to healthy habits. And with a large proportion of children above a healthy weight (currently 26%) we need to examine the broader social changes at work.

We have more and more packaged products to choose from, many dressed up as healthy. There’s a high volume of products with cute characters and giveaways on the packaging to appeal to children, coupled with nutrition claims designed to entice parents. Multinational food and drink corporations are also finding new and more insidious ways to encourage kids to eat unhealthy food.

With so many external forces influencing what to feed children, how can parents navigate this and make healthy choices?

Read more: Give in to pester power at the supermarket checkout? You're not alone

Navigating the supermarket shelves

Most parents don’t set out to feed their kids unhealthy food, but once you move away from whole fruit and veggies, convenience and clever marketing become powerful influences.

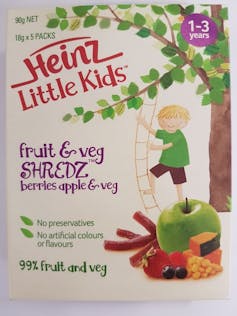

Trying to find a healthy alternative means relying on the labels on food packaging. When labels boast “99% fruit and veg”, who can blame anyone for choosing these products for their kids?

Read more: How to get children to eat a rainbow of fruit and vegetables

Brands will go to great lengths to give the impression their food is healthy. This is most starkly revealed in the recent Federal Court’s decision about misleading marketing of Heinz Little Kids Shredz, products that were up to 68% sugar.

Court documents show how there was fruit on the label, but the product contained up to 68% sugar.

ACCC/Heinz

Court documents show how there was fruit on the label, but the product contained up to 68% sugar.

ACCC/Heinz

Documents revealed in the court case also show evidence the packaging was updated to specifically create an image of a healthy and nutritious snack that would appeal to parents of toddlers.

Food manufacturers know that people associate the word “fruit” with good health. So many take advantage of this, plastering it over the packaging, especially for kids’ food. The reality is that a lot of these products actually contain sticky, sugary paste extracted from fruit; essentially a mouthful of concentrated sugar, minus the fibre.

It doesn’t matter if it’s sugar from fruit concentrate, honey, sugar cane, or the other names manufacturers use to conceal it – sugar is sugar. Parents deserve to know what’s really in the products they’re feeding their kids. Currently, that is hard to do as added sugars are not grouped together on the ingredients list, or listed separately on the nutrition information panel.

Ministers continue to avoid making added sugar labelling on products mandatory; the most recent meeting of ministers again deferred a decision. Yet there are ways to cut through marketing spin and choose the healthiest option.

Read more: Sweet power: the politics of sugar, sugary drinks and poor nutrition in Australia

Always look past the flashy promises of real fruit ingredients and make sure to read the label. Start with the ingredients list. Sugar could be hiding behind another name. As a general rule, anything with the words “paste”, “juice”, “syrup”, “cane” or, of course, “sugar” should raise a red flag.

Check the nutrition information panel to compare sugar content in products, against the “Avg per 100g” panel. Avoid anything containing more than 15g of sugar per 100g.

What should we feed children?

There’s more information than ever about what parents should be feeding children. This is leaving parents feeling not only confused, but often guilty about their children’s diets.

Despite the growing online literature and debate on what we should be feeding our children, the 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines for children are pretty clear.

Children should enjoy a wide variety of nutritious foods from the five groups every day. Resources also point out what to leave off the plate, or out of the lunchbox. But with little funding to educate the public about the guidelines, the information isn’t reaching parents.

So many food labels are hard to understand. No wonder parents find it tough working out what’s best for their kids.

from www.shutterstock.com

So many food labels are hard to understand. No wonder parents find it tough working out what’s best for their kids.

from www.shutterstock.com

But it can’t all be simply down to parents to steer children onto a healthier path.

We need leadership and action from government to encourage families to have healthier diets: better food labelling, investment in public education campaigns and tougher restrictions around junk food marketing are a start.

From the supermarket to the schoolyard

In term time, around one-third of children’s daily food intake occurs at school. So it’s vital schools follow nutrition guidelines and parents are supported to pack their kids off to school with the right sort of food.

Sorting out a child’s lunchbox shouldn’t be a soul-destroying, anxiety-inducing exercise. You don’t have to be a Masterchef to provide your child with a healthy lunch you know they’ll actually eat. Keep it simple. It doesn’t have to be a healthy muffin you spent half the night baking; a simple sandwich and some fruit will do the trick.

Read more: Health Check: how to get kids to eat healthy food

Schools need consistent guidelines and policies that support children and parents in making healthy choices. With a lack of consistent messaging and leadership, it’s no wonder there is confusion about what is healthy.

Children are exposed to pervasive and persistent junk food marketing through TV, social media or on their way to school. Then at school, there are mixed messages about what they should eat – some schools enforce no lolly policies, yet use lollies in school fundraisers.

Parents continue to face an uphill battle against the industry’s tactics to build brand awareness and encourage pester power among children. If we’re going to build a healthier world for the next generation, we need to do this through education, not guilt.

Authors: Jane Martin, Executive Manager of the Obesity Policy Coalition; Senior Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne