Businesses think they're on top of carbon risk, but tourism destinations have barely a clue

- Written by Susanne Becken, Professor of Sustainable Tourism and Director, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University

The directors of most Australian companies are well aware of the impact of carbon emissions, not only on the environment but also on their own firms as emissions-intensive industries get lumbered with taxes and regulations designed to change their behaviour.

Many are getting out of emissions-intensive activities ahead of time.

But, with honourable exceptions, Australia’s tourism industry (and the Australian authorities that support it) is rolling on as if it’s business as usual.

This could be because tourism isn’t a single industry – it is a composite, made up of many industries that together create an experience, none of which take responsibility for the whole thing.

But tourism is a huge contributor to emissions, accounting for 8% of emissions worldwide and climbing as tourism grows faster than the economies it contributes to.

Read more: The carbon footprint of tourism revealed (it's bigger than we thought)

Tourism operators are aiming for even faster growth, most of them apparently oblivious to clear evidence about what their industry is doing and the risks it is buying more heavily into.

If Australian tourist destinations were companies they would be likely to discuss the risks to their operating models from higher taxes, higher oil prices, extra regulation, and changes in consumer preferences.

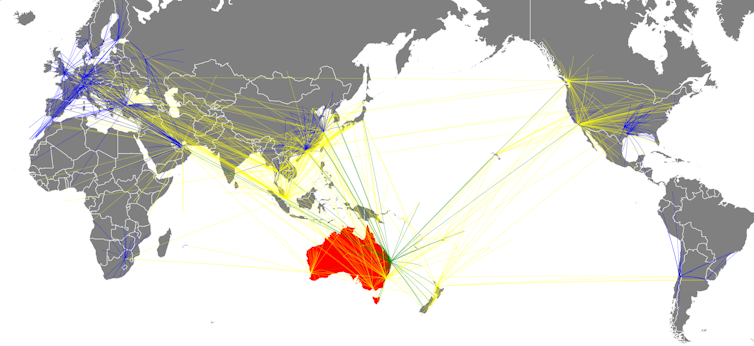

Aviation is one of the biggest tourism-related emitters, with the regions that depend on air travel heavily exposed.

But at present the destination-specific carbon footprints from aviation are not recorded, making it difficult for destinations to assess the risks.

A recent paper published in Tourism Management has attempted to fill the gap, publishing nine indicators for every airport in the world.

The biggest emitter in terms of departing passengers is Los Angeles International Airport, producing 765 kilo-tonnes of CO₂ in just one month; January 2017.

When taking into account passenger volumes, one of the airports with the highest emissions per traveller is Buenos Aires. The average person departing that airport emits 391 kilograms of CO₂ and travels a distance of 5,651 km.

The analysis used Brisbane as one of four case studies.

Most of the journeys to Brisbane are long.

Most of the journeys to Brisbane are long.

Brisbane’s share of itineraries under 400 km is very low at 0.7% (compared with destinations such as Copenhagen which has 9.1%). That indicates a relatively low potential to survive carbon risk by pivoting to public transport or electric planes, as Norway is planning to.

The average distance travelled from Brisbane is 2,852 km, a span exceeded by Auckland (4,561 km) but few other places.

As it happens, Brisbane Airport is working hard to minimise its on-the-ground environmental impact, but that’s not where its greatest threats come from.

Read more: Airline emissions and the case for a carbon tax on flight tickets

The indicators suggest that the destinations at most risk are islands, and those “off the beaten track” – the kind of destinations that tourism operators are increasingly keen to develop.

Queensland’s Outback Tourism Infrastructure Fund was established to do exactly that. It would be well advised to shift its focus to products that will survive even under scenarios of extreme decarbonisation.

They could include low-carbon transport systems and infrastructure, and a switch to domestic rather than international tourists.

Experience-based travel, slow travel and staycations are likely to become the future of tourism as holidaymakers continue to enjoy the things that tourism has always delivered, but without travelling as much and without burning as much carbon to do it.

An industry concerned about its future would start transforming now.

Read more: Sustainable shopping: is it possible to fly sustainably?

Authors: Susanne Becken, Professor of Sustainable Tourism and Director, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University