China’s new literary star had 19 jobs before ‘writer’ – including bike courier and bakery apprentice

- Written by Wanning Sun, Professor of Media and Cultural Studies, University of Technology Sydney

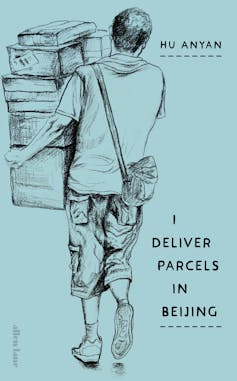

Delivering parcels is just one of the 19 different jobs Hu Anyan cycles through over 20 years, as tracked in his Chinese bestseller I Deliver Parcels in Beijing. He also tries his luck working as a convenience-store clerk, a cleaner and in a bike shop, a warehouse, a vegetable market and even an anime design company – always at the very bottom of the ladder.

Review: I Deliver Parcels in Beijing – Hu Anyan (Allen Lane)

Some jobs last weeks, some days, some barely survive the training shift. Bosses disappear, wages evaporate, contracts turn out to be imaginary and rules are invented on the spot. With a blend of hope and resignation, Hu repeatedly comes to realise the true qualifications for survival in the city are a strong back, a flexible sense of dignity and a high tolerance for absurdity.

Hu, now aged 47, grew up in Guangzhou, a major city in south China. He has worked in cities big and small, including a brief stint across the border in Vietnam.

They are “places with apparent unlimited potential for development, yet I seemed to have gotten nowhere,” he writes. They promise opportunity, then charge rent on his naivety and optimism. He seems to move through the world with a certain innocence about how it truly works, yet possesses an uncommon capacity for deep, searching reflection.

He writes with dry humour and an eye for the absurd – security guards guarding nothing, managers creating chaos and delivery algorithms ruling lives with godlike indifference. But he also writes like a field researcher issued a hard hat instead of a research grant. His prose has a forensic, documentary precision – wages counted to the cents, shifts timed, fines itemised, and injustices recorded without melodrama.

When he completed his trial as a parcel deliverer, he writes:

an assistant foreman […] told me that although the probationary period wasn’t paid, he would make it up by giving me three extra days of vacation. […] But it wasn’t even a month before the same guy had a dispute with the other foreman and quit. No one mentioned those paid days off ever again.

China’s ‘development didn’t suit me’

This reporting of everyday injustice at work is peppered with occasional philosophical reflections on human nature and the meaning of work. He calmly observes of mean and unhelpful co-workers: “Selflessness may be a noble virtue, but I suppose it isn’t fundamental to being human.”

The real charm is his tone. Even when dealing with exploitation, Hu delivers it with light-footed sarcasm, letting absurdity do the heavy lifting. Writing about heavy workload in the delivery company he works for, he simply comments “capitalists aren’t known for sympathising with workers”.

At times, he reveals his battles with social anxiety, depression and occasional bouts of illness. In one memorable scene, he describes going back and forth between hospitals, community clinics and small medical offices, carefully comparing prices before settling on where to get an IV drip to bring his fever down.

That kind of careful penny-pinching, being unable to justify spending even on one’s own health, feels painfully familiar to anyone trying to survive on very little.

Hu’s story is a personal one about structural inequality and everyday injustice. But he doesn’t sound resentful that China’s economic growth hasn’t benefited him. He just states, matter-of-factly, that China’s “development didn’t suit me”.

His personal account also functions as a practical lesson in the political economy of labour. In that sense, the lesson is not uniquely Chinese. Rather than relying on theories of profit and value, he uses his experience as a courier to show how the gig economy of late capitalism operates globally.

He meticulously calculates how the supposed average monthly pay of 7,000 yuan a month (around A$1,435) he could expect to earn translates in reality. It means working 26 days a month, 11 hours a day – to earn 30 yuan (A$6.16) an hour and 0.5 yuan (ten cents) a minute.

I had to complete a delivery every four minutes in order not to run at a loss. If that becomes unworkable, I would have to consider a change of job.

‘Oddly soothing’

For urban educated readers, both in China and elsewhere, who are crushed by emails, mortgages, childcare and performance anxiety, it can be oddly soothing to read about a life lived under more precarious conditions.

Hu’s calm endurance could work like a psychological release valve – things are hard, yes, but not this hard. The result lets middle-class readers feel ethically awake without feeling accused. This makes the book as reassuring as it is unsettling.

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is also popular with Hu’s social peers – the urban underclasses and rural migrant workers: it shows that their struggles and small victories are worthy of being recorded and remembered.

A key, albeit implicit, theme circulating the book is unequal access to social mobility. Each of the 19 jobs Hu cycled through may look different on the surface, but rather than climbing a social ladder, he merely shuffles horizontally, stagnating on the same rung: “twelve years have passed, and with the same workload as before, my pay was somehow still lower”.

There is much musing about the meaning of freedom in the book. But freedom, for Hu, is not about the right to vote, but to choose who one wants to be, rather than what society expects one to become.

There’s no cataloguing of human rights abuses – the familiar trope of English-language coverage of China. Nor is the book a sociological exercise by an intellectual, for whom Hu’s world might be an object of study. And it certainly isn’t some diasporic Chinese writer’s rendition of China, often calibrated to the expectations of festival-going, liberal middle-class readers abroad.

Instead, the book speaks from inside the experience it describes, with no apparent desire to translate itself – at least initially – into the moral or political idioms readers might expect. That’s precisely where its quiet power lies.

It doesn’t tell you what to think about China – it shows you a life you would otherwise almost never get to see. The translation, superbly done, helps enhance this objective.

The luxury of being noticed

Like worker-poet Zheng Xiaoqiong and worker-photographer Zhan Youbing, Hu the worker-writer becomes a self-appointed “surrogate ethnographer”, patiently recording rules, rhythms, hierarchies, and survival strategies from the inside. He produces not theory, but something more valuable: reality, rendered with authenticity and credibility.

“I often sat in Jingtong Roosevelt Plaza after finishing my deliveries and watched the passers-by and the salespeople in stores, and the different delivery drivers back and forth,” he writes. “Mostly I supposed they were numb, thinking nothing at all, mechanically going about their days like I once did.”

Social researchers outside China dream of accessing the trove of evidence-based, granular, situated knowledge this book contains – but they rarely do.

Hu is one of the millions of internal labour migrants in China who struggle to survive at the bottom of the social ladder – and a rare case of a worker who became a recognised writer. He has published two books since this one.

His rise was not the result of structural change, but exceptional literary talent and sharp intellectual acuity. Meanwhile, the great majority of China’s urban underclasses and rural migrant workers remain locked in the kind of precarious, exhausting existence Hu describes – without the chance to turn their experiences into art, and without the luxury of being noticed at all.

Authors: Wanning Sun, Professor of Media and Cultural Studies, University of Technology Sydney

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing is also popular with Hu’s social peers – the urban underclasses and rural migrant workers: it shows that their struggles and small victories are worthy of being recorded and remembered.

A key, albeit implicit, theme circulating the book is unequal access to social mobility. Each of the 19 jobs Hu cycled through may look different on the surface, but rather than climbing a social ladder, he merely shuffles horizontally, stagnating on the same rung: “twelve years have passed, and with the same workload as before, my pay was somehow still lower”.

There is much musing about the meaning of freedom in the book. But freedom, for Hu, is not about the right to vote, but to choose who one wants to be, rather than what society expects one to become.

There’s no cataloguing of human rights abuses – the familiar trope of English-language coverage of China. Nor is the book a sociological exercise by an intellectual, for whom Hu’s world might be an object of study. And it certainly isn’t some diasporic Chinese writer’s rendition of China, often calibrated to the expectations of festival-going, liberal middle-class readers abroad.

Instead, the book speaks from inside the experience it describes, with no apparent desire to translate itself – at least initially – into the moral or political idioms readers might expect. That’s precisely where its quiet power lies.

It doesn’t tell you what to think about China – it shows you a life you would otherwise almost never get to see. The translation, superbly done, helps enhance this objective.

The luxury of being noticed

Like worker-poet Zheng Xiaoqiong and worker-photographer Zhan Youbing, Hu the worker-writer becomes a self-appointed “surrogate ethnographer”, patiently recording rules, rhythms, hierarchies, and survival strategies from the inside. He produces not theory, but something more valuable: reality, rendered with authenticity and credibility.

“I often sat in Jingtong Roosevelt Plaza after finishing my deliveries and watched the passers-by and the salespeople in stores, and the different delivery drivers back and forth,” he writes. “Mostly I supposed they were numb, thinking nothing at all, mechanically going about their days like I once did.”

Social researchers outside China dream of accessing the trove of evidence-based, granular, situated knowledge this book contains – but they rarely do.

Hu is one of the millions of internal labour migrants in China who struggle to survive at the bottom of the social ladder – and a rare case of a worker who became a recognised writer. He has published two books since this one.

His rise was not the result of structural change, but exceptional literary talent and sharp intellectual acuity. Meanwhile, the great majority of China’s urban underclasses and rural migrant workers remain locked in the kind of precarious, exhausting existence Hu describes – without the chance to turn their experiences into art, and without the luxury of being noticed at all.

Authors: Wanning Sun, Professor of Media and Cultural Studies, University of Technology Sydney