Like Jane Eyre, I’ve been seen as unconventional and abnormal. I’m autistic – is she too?

- Written by Chloe Riley, Doctoral Candidate, Creative Writing, Australian National University

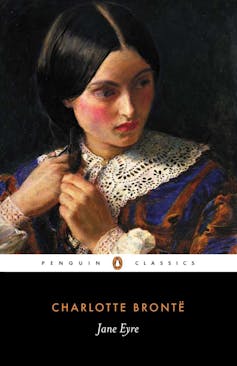

Nearly 200 years since Charlotte Brontë published Jane Eyre, her unconventional orphan Jane – with her intense emotions and sense of injustice – continues to captivate and intrigue readers.

It’s the story of a girl who rises above her social station by becoming the governess (later, wife) to her wealthy Byronic master, Edward Fairfax Rochester. Brontë’s heroine “horrified the Victorians” with her “hunger, rebellion, and rage”. Today, she is hailed as a feminist icon for those same qualities.

As an autistic woman*, I have long felt a particular affinity to the character of Jane Eyre. Like Jane, I have been perceived as unconventional and abnormal. I, too, experienced a childhood of unintentional error, in which “I dared commit no fault: I strove to fulfil every duty”.

But despite my efforts, I frequently found myself getting into trouble. I would speak directly and honestly, causing offence without intention. I would ask clarifying questions which were perceived as personal attacks. I, too, was perceived as “naughty and tiresome”. I often felt I was “not like other girls”.

As an adult, writing my master’s thesis on Jane Eyre, I was haunted by my undiagnosed autism. It threatened to escape at any moment – much like Bertha, Rochester’s mad wife imprisoned in the attic. A family secret. Through a lifetime of learning to mask – to conceal my “externally noticeable” autistic traits – I built a kind of attic within myself. Inside it, my autism, like Bertha, fought against its incarceration, threatening to reveal itself.

After I received my diagnoses of autism and ADHD in 2022, I began to see Brontë’s novel in a different light. Then, I discovered that reading Jane Eyre as autistic is not new.

Jane Eyre, autism, and madness

In 2008, literary studies scholar Julia Miele Rodas first showed how Jane Eyre can be interpreted as autistic. Specialising in disability studies and Victorian fiction, Rodas later wrote that Charlotte Brontë’s narrative voice “resonates with autism”.

Charlotte Bronte.

Charlotte Bronte, painted by her brother Patrick Bramwell

But if Jane is also neurodivergent, Bertha’s role as Jane’s “secret self” goes much deeper. Through her persistent “haunting”, Bertha enacts the psychological torment that comes with masking – the constant fight to suppress one’s natural characteristics.

If Jane is autistic, the neurodivergent “madwoman” Bertha is a physical reminder of the real “secret self” Jane represses behind her masking. She represents a plausible alternative life Jane might have lived had she not been able to mask, acting as a cautionary tale of the dangers of unmasking.

Bertha is incarcerated because she has been unable to conceal her neurodivergence and heightened emotional distress. Her only escape from imprisonment is through death – a fate shared by the other neurodivergent figure in the text, Helen Burns, also unable to mask. For Helen Burns, this fate is even welcomed, as she believes her life would have been one of “great sufferings” with her being “continuously at fault”.

Literary scholar Marta Caminero-Santangelo, author of The Madwoman Can’t Speak, argues “to achieve happiness, Jane must learn to separate herself in all ways from Bertha”. She must “stifle and finally kill the Bertha in her”.

It is not enough for the autistic Jane to conceal her neurodivergence. She must somehow destroy it. Not only is this impossible: it embodies the harmful idea that autism is something that can and should be “cured”.

Leaving behind the mask

It is hard to know if Charlotte Brontë believed this “secret self” should be killed.

Brontë was notorious for disrupting the “status quo”, yet was never “consciously” able “to define the full meaning of achieved freedom”, write Gilbert and Gubar. They suggest this may be because neither Brontë, nor her contemporaries, “could adequately describe” such “a society so drastically altered” from their own.

It would seem, in order to rescue Bertha from the attic – to liberate the “secret self” in a way other than death – a different world must first be made. One where neurodivergence can be accepted. Visible. Unmasked.

This world may be beyond the imagination of a mid-19th century writer, even a Brontë. But it is more conceivable in a world where neuro-affirming spaces have begun to emerge, along with the growth of a strengthening Autistic community.

Jane Eyre continues to speak to a shared experience among neurodivergent women: the collective struggle to survive a patriarchy that weaponises ableism against us.

Widely read as the story of a woman learning to “govern” and eventually “kill” her passionate, angry, “secret self”, Jane Eyre can be interpreted more strongly – more accurately, I believe – as an autistic woman’s story.

Note: My pronouns are they/she. I use the term “woman” loosely to describe my experience as someone who has encountered womanhood, rather than a (completely) accurate descriptor of my gender.

Authors: Chloe Riley, Doctoral Candidate, Creative Writing, Australian National University

Charlotte Bronte.

Charlotte Bronte, painted by her brother Patrick Bramwell

But if Jane is also neurodivergent, Bertha’s role as Jane’s “secret self” goes much deeper. Through her persistent “haunting”, Bertha enacts the psychological torment that comes with masking – the constant fight to suppress one’s natural characteristics.

If Jane is autistic, the neurodivergent “madwoman” Bertha is a physical reminder of the real “secret self” Jane represses behind her masking. She represents a plausible alternative life Jane might have lived had she not been able to mask, acting as a cautionary tale of the dangers of unmasking.

Bertha is incarcerated because she has been unable to conceal her neurodivergence and heightened emotional distress. Her only escape from imprisonment is through death – a fate shared by the other neurodivergent figure in the text, Helen Burns, also unable to mask. For Helen Burns, this fate is even welcomed, as she believes her life would have been one of “great sufferings” with her being “continuously at fault”.

Literary scholar Marta Caminero-Santangelo, author of The Madwoman Can’t Speak, argues “to achieve happiness, Jane must learn to separate herself in all ways from Bertha”. She must “stifle and finally kill the Bertha in her”.

It is not enough for the autistic Jane to conceal her neurodivergence. She must somehow destroy it. Not only is this impossible: it embodies the harmful idea that autism is something that can and should be “cured”.

Leaving behind the mask

It is hard to know if Charlotte Brontë believed this “secret self” should be killed.

Brontë was notorious for disrupting the “status quo”, yet was never “consciously” able “to define the full meaning of achieved freedom”, write Gilbert and Gubar. They suggest this may be because neither Brontë, nor her contemporaries, “could adequately describe” such “a society so drastically altered” from their own.

It would seem, in order to rescue Bertha from the attic – to liberate the “secret self” in a way other than death – a different world must first be made. One where neurodivergence can be accepted. Visible. Unmasked.

This world may be beyond the imagination of a mid-19th century writer, even a Brontë. But it is more conceivable in a world where neuro-affirming spaces have begun to emerge, along with the growth of a strengthening Autistic community.

Jane Eyre continues to speak to a shared experience among neurodivergent women: the collective struggle to survive a patriarchy that weaponises ableism against us.

Widely read as the story of a woman learning to “govern” and eventually “kill” her passionate, angry, “secret self”, Jane Eyre can be interpreted more strongly – more accurately, I believe – as an autistic woman’s story.

Note: My pronouns are they/she. I use the term “woman” loosely to describe my experience as someone who has encountered womanhood, rather than a (completely) accurate descriptor of my gender.

Authors: Chloe Riley, Doctoral Candidate, Creative Writing, Australian National University