An Antarctic ‘polar thriller’ and a neurodivergent novel imagine a climate changed future

- Written by Caitlin Macdonald, Doctor of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, University of Sydney

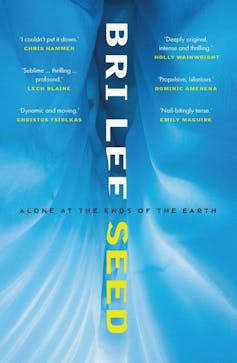

Two new Australian novels imagine how we might live in a climate‑changed future. Bri Lee’s Seed explores antinatalism in an Antarctic seed vault. And Rose Michael’s Else follows a mother and daughter improvising survival on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula.

Together, these novels ask what we owe future generations – and what forms of care remain possible when the planet itself becomes precarious.

Antinatalism is the view that bringing new humans into the world is morally suspect because life entails unavoidable harm. It has become increasingly visible alongside escalating climate anxiety. In fiction, the question tends to crystallise around the figure of “the child as future”: should we burden the planet with more lives, and burden those lives with the planet we have made?

Review: Seed – Bri Lee (Summit); Else – Rose Michael (Spineless Wonders)

Alice Robinson’s 2024 novel If You Go pushed that question into speculative territory. In it, a mother wakes a century after being cryogenically suspended, and must reckon with the failure to prepare her children for a world remade by climate and social collapse.

Lee’s Seed and Michael’s Else approach the matter of future generations from opposite directions. Seed situates its enquiry inside an ambitious thriller: a secret Antarctic seed bank, a month‑long mission and communications failures.

Else is a lyrical, experimental novella charting seasonal adaptation as a mother (Leisl) and daughter (Else) move down the “Ninch” – local slang for the Mornington Peninsula – as floods and fires reconfigure their world.

Both books are recognisably climate fiction, but they part ways on what climate ethics look like in practice. Lee’s novel sits alongside Charlotte McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore, published earlier this year, in its use of a seed vault as a narrative device – a high‑stakes backdrop where questions of what we choose to save, and what we sacrifice, become urgent.

McConaghy frames those choices through family bonds and a plea for climate action; Seed filters them through the lens of antinatalism. Seed formalises refusal through the narrator’s principled insistence on not reproducing, while Else imagines care as improvisation: a family learning to read Country and attune to non‑human signals in a context of uncertainty.

Antarctica as ethical sanctuary

Lee’s narrator, Mitch, is a biologist and outspoken antinatalist. His sixth stint on “Anarctos”, a secret Antarctic seed vault, becomes a study in paranoia.

Mitch reveres the ice for its “lavish indifference to human life” and treats Antarctica like an ethical sanctuary, a place where the apathy of the landscape might absolve him of human entanglements. That posture is tested by small anomalies: a cat that shouldn’t be there, radios that don’t behave and penguins appearing where they shouldn’t be.

Rose Michael’s climate novel is about language and attention.

Holly Campbell

Michael plays with dialogue as “trade”: one that is learned. The novel’s recurring irony is that human language is not the dominant language on Earth. In a world that is “more sea, now”, bioluminescent communication becomes the planet’s primary speech. This suggests humans are guests in a more‑than‑human conversation. The novel advocates a practice: adapt; listen; tune your body to animal signs; accept that “progress” isn’t inevitably positive. And keep asking: “what right do we have to feel at home?”

While Seed is largely interior, experienced through Mitch’s self‑justifying voice, Else distributes attention outward: to seasons, shorelines, currents and the phenomenology of weather. Its ethics are ecological rather than abstract. Children are not only the burden of future harm; they are the learners who might help families survive by noticing differently.

Comparatively, the books articulate two answers to the future‑child problem. In Seed, the child is a moral focal point adult certainty breaks against. Mitch’s ex‑wife’s pregnancy sharpens every antinatalist claim, exposes contradictions in his care for a non‑human “orphan” and forces a reckoning with what he is willing to betray to keep his position intact. The Antarctic vault literalises the fantasy of preservation without people – seeds saved from us, not for us.

Rose Michael’s climate novel is about language and attention.

Holly Campbell

Michael plays with dialogue as “trade”: one that is learned. The novel’s recurring irony is that human language is not the dominant language on Earth. In a world that is “more sea, now”, bioluminescent communication becomes the planet’s primary speech. This suggests humans are guests in a more‑than‑human conversation. The novel advocates a practice: adapt; listen; tune your body to animal signs; accept that “progress” isn’t inevitably positive. And keep asking: “what right do we have to feel at home?”

While Seed is largely interior, experienced through Mitch’s self‑justifying voice, Else distributes attention outward: to seasons, shorelines, currents and the phenomenology of weather. Its ethics are ecological rather than abstract. Children are not only the burden of future harm; they are the learners who might help families survive by noticing differently.

Comparatively, the books articulate two answers to the future‑child problem. In Seed, the child is a moral focal point adult certainty breaks against. Mitch’s ex‑wife’s pregnancy sharpens every antinatalist claim, exposes contradictions in his care for a non‑human “orphan” and forces a reckoning with what he is willing to betray to keep his position intact. The Antarctic vault literalises the fantasy of preservation without people – seeds saved from us, not for us.

In Else, the child is not an emblem, but a collaborator. Else’s neurodivergent ways of seeing and speaking are not problems to be fixed; they are survival literacies. As climate events stack up, the family’s capacity to interpret animal and oceanic signals becomes their ethics: they are neither heroic nor despairing, but sustained. What is preserved is seasonal knowledge and the habit of noticing.

This divergence matters because climate ethics can drift toward abstraction.

Antinatalism often positions itself as a clean solution: fewer people, less harm. But fiction reminds us solutions are lived by specific bodies in messy quarters.

Seed is strongest when it reveals the gap between Mitch’s theory and his embodied care (for animals, for his ex‑wife, for a colleague with different stakes). Else is strongest when it makes care operational: month‑by‑month decisions, imperfect communication and a practice of belonging that refuses simple optimism.

Making ethical bets

Neither novel offers neat closure. The point is not certainty, but how we proceed. Do we make ethical bets under uncertainty, or do we rehearse attention until it becomes habit? In an era when we are asked to sit with contradiction, I find Else’s ethic more generative: it imagines care that can continue without perfect confidence.

Australian climate fiction increasingly wrestles with responsibility and the politics of care. Seed and Else join works that publicly situate private decisions. Seed contributes a sharp character study of antinatalism under pressure. Else deepens the imaginative repertoire for adaptation – especially through neurodivergence and embodied, place‑based knowledge.

Climate futures will likely need both technological preservation and social adaptation – but these novels suggest ethics without care cannot hold, and care without attention cannot survive.

Seed’s ideas are arresting and its Antarctic setting and outpost paranoia deliver genuine momentum, but its ethical inquiry sometimes hardens into a posture that constrains the book’s capacities for care.

Else feels modest but quietly radical: a mother–daughter story that listens, names debts to Country and imagines hope as something practised. Its fragmented syntax, unusual punctuation and shifts in voice demand patience.

Read together, these novels clarify a live question: not simply whether to have children, but how to remain responsible to future humans – and the more-than-human – as the climate shifts around us.

Authors: Caitlin Macdonald, Doctor of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, University of Sydney

In Else, the child is not an emblem, but a collaborator. Else’s neurodivergent ways of seeing and speaking are not problems to be fixed; they are survival literacies. As climate events stack up, the family’s capacity to interpret animal and oceanic signals becomes their ethics: they are neither heroic nor despairing, but sustained. What is preserved is seasonal knowledge and the habit of noticing.

This divergence matters because climate ethics can drift toward abstraction.

Antinatalism often positions itself as a clean solution: fewer people, less harm. But fiction reminds us solutions are lived by specific bodies in messy quarters.

Seed is strongest when it reveals the gap between Mitch’s theory and his embodied care (for animals, for his ex‑wife, for a colleague with different stakes). Else is strongest when it makes care operational: month‑by‑month decisions, imperfect communication and a practice of belonging that refuses simple optimism.

Making ethical bets

Neither novel offers neat closure. The point is not certainty, but how we proceed. Do we make ethical bets under uncertainty, or do we rehearse attention until it becomes habit? In an era when we are asked to sit with contradiction, I find Else’s ethic more generative: it imagines care that can continue without perfect confidence.

Australian climate fiction increasingly wrestles with responsibility and the politics of care. Seed and Else join works that publicly situate private decisions. Seed contributes a sharp character study of antinatalism under pressure. Else deepens the imaginative repertoire for adaptation – especially through neurodivergence and embodied, place‑based knowledge.

Climate futures will likely need both technological preservation and social adaptation – but these novels suggest ethics without care cannot hold, and care without attention cannot survive.

Seed’s ideas are arresting and its Antarctic setting and outpost paranoia deliver genuine momentum, but its ethical inquiry sometimes hardens into a posture that constrains the book’s capacities for care.

Else feels modest but quietly radical: a mother–daughter story that listens, names debts to Country and imagines hope as something practised. Its fragmented syntax, unusual punctuation and shifts in voice demand patience.

Read together, these novels clarify a live question: not simply whether to have children, but how to remain responsible to future humans – and the more-than-human – as the climate shifts around us.

Authors: Caitlin Macdonald, Doctor of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, University of Sydney