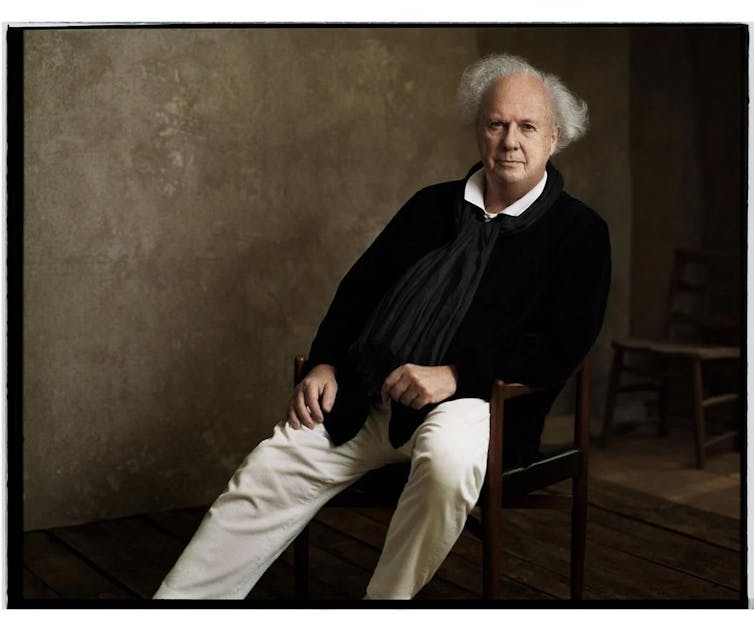

Graydon Carter hired Christopher Hitchens, pissed off Trump and revealed Deep Throat. He calls himself a ‘beta male’

- Written by Julian Novitz, Senior Lecturer, Writing, Department of Media and Communication, Swinburne University of Technology

The editor of Vanity Fair, Radhika Jones, is stepping down after seven years. Amid the media buzz about who might take her role – long considered a plum one – is a surprising question. “Is it still a good job?” asked the New York Times last week.

Some magazine editors have said no, one even saying “I wouldn’t touch that job”. But Jones’ immediate predecessor, Graydon Carter, says it’s “still a great job for an enterprising editor”, though the golden age of magazines – including Vanity Fair – is clearly over.

Carter’s new memoir recounts his time as editor from 1992 to 2017, during the magazine’s glory days. It’s full of stories about editors and writers who comfortably stalked the halls of power. They rubbed shoulders with tycoons and celebrities, attracted both reverence and apoplectic rage, and were handsomely paid for it.

Review: When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines – Graydon Carter (Grove Press)

When the Going Was Good is an apt title for a book about the “golden age of magazines”. Carter’s memoir focuses on his time at Vanity Fair, but also includes stints at Time magazine, where he got his first taste of “expense account life”, and as co-founder of iconic satirical magazine Spy, where he first described rising tycoon Donald Trump as a “short-fingered vulgarian”.

As Carter notes in his memoir, the glory days of the print magazines have passed. What can he tell us about their heyday, and the future of long-form journalism?

Golden days

For an editor with a few horror stories about writers who exceed their word count – one would apparently turn in 70,000-word “vomit drafts” – Carter doesn’t exactly make a virtue of concision. The opening chapters linger on his upbringing in Ottawa, and it takes roughly 50 pages to arrive at the subject of magazine work.

At university, he joined a literary magazine (the Canadian Review) on a whim, and swiftly became its editor. Over six years, he grew its circulation to an impressive 50,000 copies. When the Canadian Review folded in 1978, Carter moved to New York.

This is where When the Going Was Good picks up. Carter succeeds in conveying the excitement and possibility of this period. He got a job at Time when it was still the “magazine of yore, the weekly that could move the market and influence presidential elections”, and not the “digital husk” he now considers it.